El lenguaje de la polipatología

Este es un documento vivo (más información) titulado "El lenguaje de la Polipatología" y desarrollado en el espacio del equipo Web de trabajo colaborativo en el lenguaje de la polipatología.

Se ha incluido como capítulo 2 en el libro sobre polipatología (índice y PDF del libro; PDF del capítulo en inglés, PDF del capítulo en español).

Puede seguir todos los comentarios aquí o suscribirse a su canal RSS.

Para cualquier comentario, duda, sugerencia o si necesita soporte técnico, por favor no dude en contactar con nosotros en info@opimec.org

A continuación, ¡DISFRUTE del contenido del documento y PARTICIPE en mejorar el conocimiento sobre la polipatología!

Tabla de contenidos

- Viñeta: ¿Cómo podría ser?

- Resumen

- ¿Por qué es importante este tema?

- ¿Qué sabemos?

- Comorbilidad

- Polipatología (o poli-patología)

- Morbilidad confluente

- Herramientas de valoración

- El índice de Charlson

- La escala CIRS (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, Escala de valoración acumulativa de enfermedades)

- El ICED (Index of Coexisting Disease, Índice de enfermedades coexistentes)

- El índice de Kaplan ó de Kaplan-Feinstein

- Otros instrumentos pronósticos

- ¿Qué hay que saber?

- ¿Qué estrategias innovadoras podrían acortar las distancias?

- Contribuyentes

- Referencias bibliográficas (pulse aquí para acceder)

- Licencia Creative Commons

Use el botón “pantalla completa” ![]() para aumentar el tamaño de la ventana y poder editar con mayor comodidad.

para aumentar el tamaño de la ventana y poder editar con mayor comodidad.

En la esquina superior izquierda elija el formato del texto seleccionando en el menú desplegable:

- Párrafo: para texto normal

-Capítulo de primer nivel, de segundo, de tercero: para resaltar los títulos de las secciones y construir el índice. Aquellos enunciados que resalte con este formato aparecerán automáticamente en el índice del documento (tabla de contenidos).

Use las opciones Ctrl V o CMD V para pegar y Ctrl C/CMD C para copiar, Ctrl X/CMD X para cortar (en algunos navegadores no funcionan los botones habilitados para ello)

Al finalizar la edición no olvide guardar los cambios pulsando el botón inferior izquierdo Guardar o Cancelar si no quiere guardar los cambios efectuados

Más información aquí

Viñeta: ¿Cómo podría ser?

Paula, una estudiante de medicina de 23 años, está entrevistando y examinando al Sr. Gupta, quien tiene una larga historia de diabetes, artritis y enfermedad de Parkinson. Como es normal ahora, se asegura de que las diez cámaras que hay en el consultorio graben cada una de sus acciones, así como la conversación con el Sr. Gupta. Aún le resulta difícil de creer que su abuelo tuviera que utilizar lápiz y papel para tomar nota de la historia médica de un paciente, o que su padre (médico también, parece que es cosa de familia) tuviese que escribir sus impresiones con la ayuda de un teclado y un ratón en lo que entonces se llamaba un ordenador.

Está muy agradecida al esfuerzo global sin precedentes que se llevó a cabo en la segunda década del siglo XXI para desarrollar una taxonomía que ahora permite que cualquier sistema de información sanitaria grabe, codifique y clasifique todas su actividades clínicas y de investigación, y haga un informe de sus resultados, automáticamente, sin tener que realizar ningún esfuerzo adicional por su parte. También está encantada de saber que ella no es parte de una minoría privilegiada: cualquier profesional de la salud, investigador, legislador, gestor, patrocinador y cualquier persona interesada en las enfermedades crónicas múltiples utiliza esa taxonomía, que se encuentra disponible en cualquier lugar del mundo, de forma gratuita, en más de cien idiomas y a través de múltiples formatos, plataformas tecnológicas y medios de comunicación. Igualmente, está orgullosa del hecho de que, de acuerdo con el carácter abierto que inspiró su creación, ella o cualquier otra persona puede modificar la taxonomía, desde cualquier lugar del planeta, en cualquier momento. Sabe que sus sugerencias serán estudiadas a fondo por las personas elegidas para garantizar que la taxonomía refleje las necesidades de sus usuarios y contribuya a un sistema sanitario sostenible y centrado en las personas.

Resumen

- No existe una terminología aceptada o aceptable para identificar, caracterizar describir, codificar y clasificar lo que les ocurre a las personas que viven con múltiples enfermedades crónicas.

- Una terminología de ese tipo podría tener un papel decisivo en los esfuerzos que intentan transformar la gestión y en la investigación en esos casos complejos.

- Los recursos existentes para codificar y clasificar se podrían complementar para captar la naturaleza llena de matices de las enfermedades crónicas múltiples.

- Comorbilidad es un término que aparece en la mayoría de terminologías, pero aparece para referirse, principalmente, a múltiples enfermedades relacionadas con una enfermedad principal, o que son secundarias respecto a esa enfermedad.

- Otros términos más nuevos, como pluripatologíapolipatología pueden resultar más adecuados, ya que tienden a centrarse más en casos en los que no existe una enfermedad primaria o dominante.

- Cualquier terminología o taxonomía debe tener en cuenta términos de gran relevancia para las enfermedades crónicas múltiples, como fragilidad, discapacidad y complejidad.

- Internet y, especialmente, los potentes recursos que ofrece la web 2.0, como OPIMEC, podrían fomentar esfuerzos globales de cooperación que podrían acelerar el desarrollo de una taxonomía sólida y ampliamente aceptada para las enfermedades crónicas múltiples.

¿Por qué es importante este tema?

Sin unas herramientas válidas, fáciles de usar y ampliamente aceptadas para captar y comunicar lo que les ocurre a las personas que viven con múltiples enfermedades crónicas, a los legisladores, médicos, investigadores, gestores, pacientes, cuidadores y otros grupos interesados les resultaría muy difícil continuar con los esfuerzos sin precedentes que se necesitan para permitir que el sistema sanitario satisfaga las necesidades de esta población tan desatendida.

¿Qué sabemos?

La terminología que se ha utilizado tradicionalmente en relación con pacientes que sufren enfermedades crónicas suele ser un reflejo de los compartimentos estancos en que se estructura el sistema sanitario, que se centra en las necesidades de enfermedades u órganos individuales.

El escaso trabajo que se ha realizado en relación con las enfermedades crónicas múltiples se ha centrado principalmente en la comorbilidad, entendida, sobre todo, en términos de una enfermedad primaria y los trastornos asociados con ella (véase más abajo). También se usan con frecuencia otros términos, más relacionados con los servicios sanitarios o con el estado general de salud, como “viajeros habituales”s (del inglés, frequent Flyers, que se refiere a pacientes que visitan centros de atencion frecuentemente), hiperfrecuentadores, polimedicados, fragilidad y discapacidad. Sin embargo, hay una falta de estandarización en cuanto a la terminología empleada, tanto por médicos como por investigadores, en este campo. Falta un tesauro de enfermedades polipatológicas, una taxonomía no ambigua con definiciones de los términos válidas, fáciles de entender y ampliamente aceptadas, y un marco claro diseñado para fomentar el estudio de las relaciones existentes entre ellos.

La lista de encabezamientos de materias de medicina (MeSH, en siglas en inglés) de la Biblioteca Nacional de Medicina de Estados Unidos es la que ofrece la cobertura más amplia de conceptos relacionados con la salud; sin embargo, carece de muchos términos relacionados con los aspectos a los que se enfrentan los pacientes que viven con múltiples enfermedades crónicas. La Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades (conocida como ICD, International Classification of Diseases) de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) goza de amplia aceptación en muchos sistemas sanitarios de todo el mundo, pero es poco más que una lista ordenada unidimensional de términos que describen conceptos médicos, con poca relevancia en cuanto a los pacientes con enfermedades crónicas complejas. Incluso SNOMED CT (siglas en inglés para Nomenclatura Sistematizada de Términos en Medicina Clínica), el vocabulario clínico más exhaustivo disponible en cualquier idioma, carece de términos específicos que permitan hacer una descripción clara y reproducible de los trastornos, las intervenciones y los resultados obtenidos en cualquier caso en el que coexistan dos o más enfermedades crónicas (1). El único intento significativo que se ha hecho para clasificar las intervenciones de gestión de la enfermedad a través de una taxonomía exhaustiva se propuso en 2006, en relación con las enfermedades cardiovasculares (véase el apartado “La importancia de una taxonomía común para intervenciones relacionadas con las enfermedades crónicas”) (2).

A continuación exponemos una breve descripción de los términos de uso más habitual:

Comorbilidad

En 1990, la Biblioteca Nacional de Medicina de Estados Unidos introdujo el término MeSH comorbilidad, y lo definió como la presencia de enfermedades coexistentes, o enfermedades que tienen un efecto acumulativo, a partir de un diagnóstico inicial o en referencia a una enfermedad primaria que es el objeto de estudio. Este enfoque, que pone énfasis en la existencia de una enfermedad primaria o principal y una constelación de enfermedades asociadas (que solo en ocasiones son secundarias respecto a la primaria) convierte la comorbilidad en un concepto vertical. Debido a su verticalidad, los pacientes pueden etiquetarse de forma diferente dependiendo del punto de vista del médico. Por ejemplo, a una paciente con diabetes avanzada que presenta insuficiencia cardiaca congestiva, neuropatía periférica y nefropatía incipiente se le podrían asignar diferentes enfermedades primarias dependiendo de si su caso lo lleva un endocrino, un cardiólogo, un neurólogo o un nefrólogo.

Médicos con una larga experiencia, que dedican la mayor parte de su tiempo a la gestión de pacientes con enfermedades múltiples indican que la comorbilidad se debe clasificar en tres grupos, en función de la relación existente entre la enfermedad índice y el resto de enfermedades que la acompañan (Bob Bernstein, comunicación personal):

- Aleatoria: Se trata en enfermedades que se manifiestan conjuntamente con una frecuencia que no es diferente de la que se da en esas enfermedades por separado en la población. Un ejemplo de este tipo es la coexistencia de verrugas en las manos y artrosis.

- Consecuencial: Este es el tipo habitual de comorbilidad que se incluye en la mayoría de sistemas de clasificación, y se refiere a enfermedades que son fisiopatológicamente parte de un mismo proceso, como la diabetes y la hipertensión, que se manifiestan conjuntamente con una frecuencia mucho mayor que la que podría deberse simplemente al azar. Estas comorbilidades, aunque resultan interesantes, son predecibles.

- Comorbilidad por agrupación: Esto es lo que ocurre cuando se da una agrupación no aleatoria de problemas de salud sin una causa patofisiológica subyacente clara, como sucede en el caso de la obesidad y el cáncer, por ejemplo. Este tipo de comorbilidad ofrece la posibilidad de descubrir cosas nuevas, ya sea nuevas maneras de entender ciertos aspectos de la fisiopatología, o bien una nueva apreciación de la naturaleza de la complejidad. Este término podría considerarse equivalente a polipatología, tal como se describe más abajo.

Los términos que se traducirían como multimorbilidad, polipatología o pluripatología se consideran a menudo intercambiables con comorbilidad en alemán, francés y español (3-12). Sin embargo, polipatología puede ofrecer algunas ventajas por derecho propio, como un término diferenciado de los anteriores.

Polipatología (o poli-patología)

Polipatología (también descrito como pluripatología) se utiliza habitualmente en España como un concepto complementario (no antagónico) del de comorbilidad. Este concepto ha aparecido a raíz de la necesidad de referirse de forma más holística al grupo de personas que viven con dos o más enfermedades crónicas sintomáticas. En este tipo de pacientes resulta difícil establecer una enfermedad predominante, ya que todas las que coexisten son similares en cuanto a su potencial para desestabilizar a la persona, a la vez que generan importantes retos en cuanto a su gestión. En consecuencia, es un concepto más transversal que se centra en el paciente en conjunto, y no en una enfermedad o en el profesional que atiende al paciente.

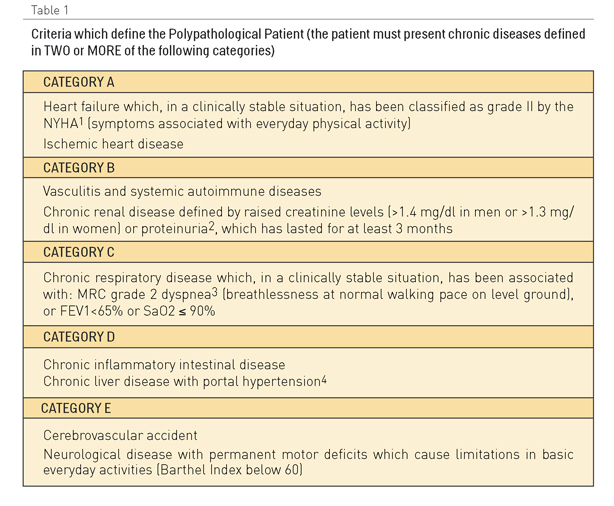

En 2002 se propuso en Andalucía una serie de criterios para la polipatología y, desde entonces, esos han sido los criterios que han adoptado varias autoridades sanitarias regionales (13), abarcando una población de más de ocho millones de personas. Su valor pronóstico se ha validado por medio de cohortes prospectivas (14) de personas con polipatología en entornos hospitalarios.

De acuerdo con estos criterios, los pacientes se definen como pluripatológicos o polipatológicos cuando tienen enfermedades crónicas que pertenecen a DOS o MÁS de las ocho categorías recogidas en la Tabla 1.

Tabla 1: Criterios definitorios de paciente pluripatológico (el paciente debe presentar enfermedades crónicas definidas en DOS ó MÁS de las siguientes categorías

1 Ligera limitación de la actividad física. La actividad física habitual le produce disnea, angina, cansancio o palpitaciones.

2 Índice albumina/Creatinina > 300 mg/g, microalbuminuria > 3mg/dl en muestra de orina o Albumina > 300 mg/dia en orina de 24 horas o > 200 microg/min

3 Incapacidad de mantener el paso de otra persona de la misma edad, caminando en llano, debido a la dificultad respiratoria o tener que para a descansar al andar en llano al propio paso.

4 Definida por la presencia de datos clínicos, analíticos, ecográficos o endoscópico.

4 Definida a partir de datos clínicos, analíticos, ecográficos y endoscópicos.

El concepto de polipatología engloba un amplio espectro clínico que abarca desde pacientes que, a consecuencia de su enfermedad, están sujetos a un alto riesgo de discapacidad, hasta pacientes que padecen varias enfermedades crónicas con síntomas continuados y frecuentes exacerbaciones que generan una demanda de atención que, en muchos casos, no encaja en los servicios tradicionales dentro del sistema sanitario.

En consecuencia, el grupo de pacientes polipatológicos no se define únicamente por la presencia de dos o más enfermedades, sino más bien por una susceptibilidad y una discapacidad clínicas especiales que conllevan una demanda frecuente de atención médica a diferentes niveles que es difícil de planificar y coordinar, debido a las exacerbaciones y la aparición de enfermedades posteriores que sitúan al paciente en una trayectoria de deterioro físico y emocional progresivo, con la pérdida gradual de autonomía y de capacidad funcional. Estos pacientes forman un grupo que tiene una especial predisposición a sufrir los efectos perjudiciales de la fragmentación y la superespecialización de los sistemas sanitarios tradicionales. Por lo tanto, podemos considerarlos centinelas o indicadores del estado de salud general del sistema sanitario, así como de su coherencia interna entre los distintos niveles.

Entonces, la polipatología, como un nuevo síndrome, puede definir a una población de pacientes con alta prevalencia en la sociedad y que presenta una complejidad clínica considerable, una vulnerabilidad, discapacidad y consumo de recursos significativos, así como una alta tasa de mortalidad a nivel tanto de atención primaria como hospitalaria, lo que pone de manifiesto la necesidad de integrar y coordinar la atención sanitaria a diferentes niveles.

De acuerdo con su Programa de Calidad y Eficacia, la Consejería de Salud de la Junta de Andalucía, en España, diseñó un proceso organizativo para optimizar la atención a las polipatologías siguiendo estrategias de gestión total de la calidad (capítulo 6). Este proceso, que desarrolló un equipo de especialistas en medicina interna, médicos de familia y enfermeras, se centra en los roles, los flujos y las mejores prácticas clínicas, todos ellos factores apoyados por un sistema de información integrado, con el objetivo fundamental de conseguir una atención médica continuada (15-16 ).

Recientemente, se estimó que la incidencia de polipatologías en las salas de medicina interna de un hospital de nivel terciario correspondía al 39% de ingresos cada mes (17). Además, este estudio mostró prospectivamente que los criterios mencionados anteriormente servían para identificar correctamente a los pacientes con discapacidad y una complejidad clínica significativa (el 35% cumplía tres o más criterios y tenía una necesidad mayor de atención médica urgente y de ingresos en el hospital), alta mortalidad (19% durante el ingreso índice) y discapacidad progresiva (deficiencia significativa y deterioro funcional durante el proceso de asistencia).

La importancia de contar con definiciones y procesos estandarizados para la gestión de los pacientes polipatológicos empieza a reflejarse en publicaciones acerca de la comorbilidad a nivel nacional, cuando se hace referencia tanto a pacientes de hospital (17-21) como a la población general (22-24).

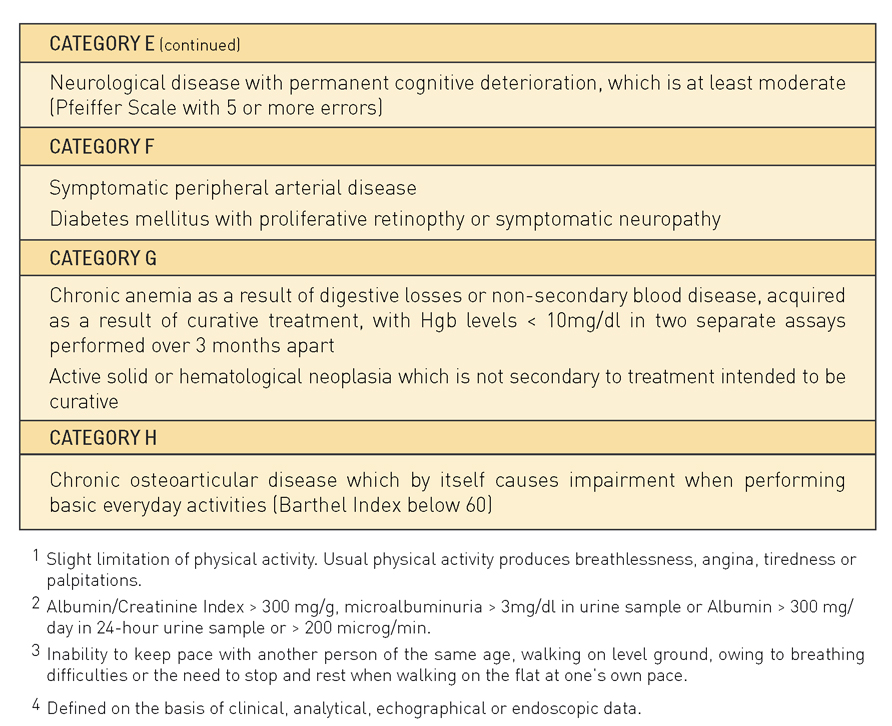

Recientemente se ha demostrado que las tasas de mortalidad entre pacientes polipatológicos hospitalizados son significativamente superiores durante la hospitalización que en pacientes que no están hospitalizados, independientemente de la causa de la hospitalización. Los factores relacionados independientemente con un pronóstico de vida más corto eran edad más avanzada y un peor estado funcional.

Además, en este tipo de pacientes, el deterioro suele ser mayor mientras permanecen en el hospital que en el caso de pacientes no polipatológicos. La figura 1 muestra los resultados de un estudio comparativo reciente acerca del deterioro funcional cuando existe polipatología y en pacientes generales durante una hospitalización convencional (24).

Figura 1. Deterioro funcional basal (medido de acuerdo con la escala de Barthel) en el ingreso y el alta de cohortes de pacientes generales y pluripatológicos

Enfermedad crónica compleja

Empleado en instituciones especializadas en enfermedades crónicas múltiples, como Bridgepoint Health, en Canadá, este es otro de los términos que ha aparecido en relación con las personas que viven con dos o más enfermedades crónicas [http://www.lifechanges.ca/complex_chroni...]. Sin embargo, la principal limitación de este término es que la pluripatología es solo un aspecto de la complejidad en estos casos. Las personas que viven con polipatologías pueden ser complejas o no, dependiendo de otros muchos factores relacionados. De hecho, la polipatología puede no ser una condición necesaria ni suficiente. Algunos pacientes pueden ser complejos con una sola enfermedad “clásica”, mientras que gestionar a otros que padezcan varias enfermedades puede ser fácil con unos cuantos recursos. Por ejemplo, una persona que viva en la calle y que solo tenga esquizofrenia es compleja, mientras que una persona estable y bien controlada con diabetes que esté además en tratamiento por hipertensión e hiperlipidemia no lo es.

En consecuencia, en pacientes complejos la carga de la enfermedad no solo depende de los problemas de salud, sino también de circunstancias sociales, culturales y medioambientales y de su estilo de vida. No se puede negar que estas circunstancias exacerbarán o aliviarán con frecuencia la carga de la enfermedad, y pueden explicar las consecuencias diferentes que situaciones clínicas idénticas tienen para distintas personas (25).

Morbilidad confluente

Se pueden asignar etiquetas diagnósticas a múltiples enfermedades coexistentes que se contabilizan y se agrupan fácilmente, a efectos epidemiológicos o para la creación de unas directrices para el ejercicio de la medicina. Sin embargo, a medida que aumenta el número de enfermedades en una persona, disminuye el valor clínico de este enfoque. Un número creciente de enfermedades va a menudo acompañado por un número creciente de medicamentos. En algún momento la confluencia de los efectos de las enfermedades y de los medicamentos prescritos es tan compleja que impide cualquier esfuerzo claro de atribuir signos o síntomas a una causa específica (26). En estos casos, el término morbilidad confluente podría permitir a los médicos y pacientes centrarse en aliviar los síntomas, en lugar de perder el tiempo en inútiles ejercicios de diagnóstico.

Herramientas de valoración

Un estudio sistemático de los métodos para medir la comorbilidad indicó que uno de ellos era simplemente un recuento de enfermedades y que otros doce eran índices (27). A continuación, veremos los que se consideraron válidos y fiables:

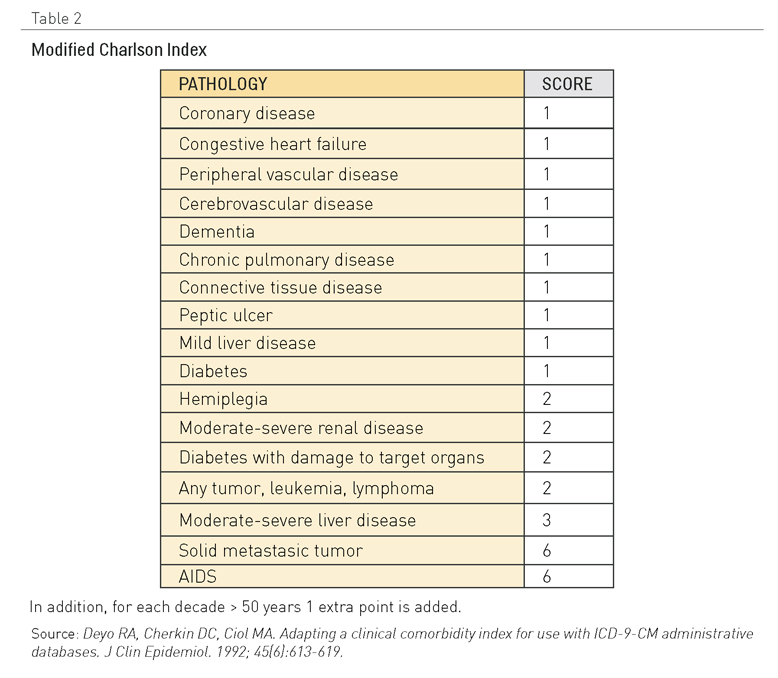

El índice de Charlson

Este es el instrumento más empleado para la valoración pronóstica en pacientes con comorbilidad. Inicialmente, se publicó en 1987 y se modificó posteriormente en 1994. La creación del índice de Charlson (28) se basó en un principio en un estudio prospectivo de 559 pacientes que correlacionaba mortalidad a un año con comorbilidad (Tabla 2). Dependiendo de la causa de mortalidad, se daba una puntuación a cada enfermedad crónica presente y, al sumar las puntuaciones, el resultado era un índice que tenía una correlación con la mortalidad.

El éxito del índice de Charlson se debe en gran medida a la modificación introducida por Deyo (29), quien lo adaptó a los códigos de diagnóstico almacenados en bases de datos administrativas con información acerca de más de 27.000 pacientes que se habían sometido a intervenciones de columna lumbar en 1985. La adaptación de Deyo del índice de Charlson se ha convertido en el índice de comorbilidad más utilizado. Es importante destacar que el estudio se basaba en una cohorte de hospital y en la mortalidad a un año. La mortalidad para cada cuartil de pacientes del estudio fue la siguiente: puntuación 0: 12%, puntuación 1-2: 26%, puntuación 3-4: 52% y puntuación 5: 85%.

Posteriormente el índice se ha validado en diferentes zonas geográficas y en diferentes grupos de pacientes con patologías concretas, y también se ha correlacionado con muchas variables como la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud, los reingresos y los costes sanitarios, entre otros.

Tabla 2. Índice de Charlson modificado

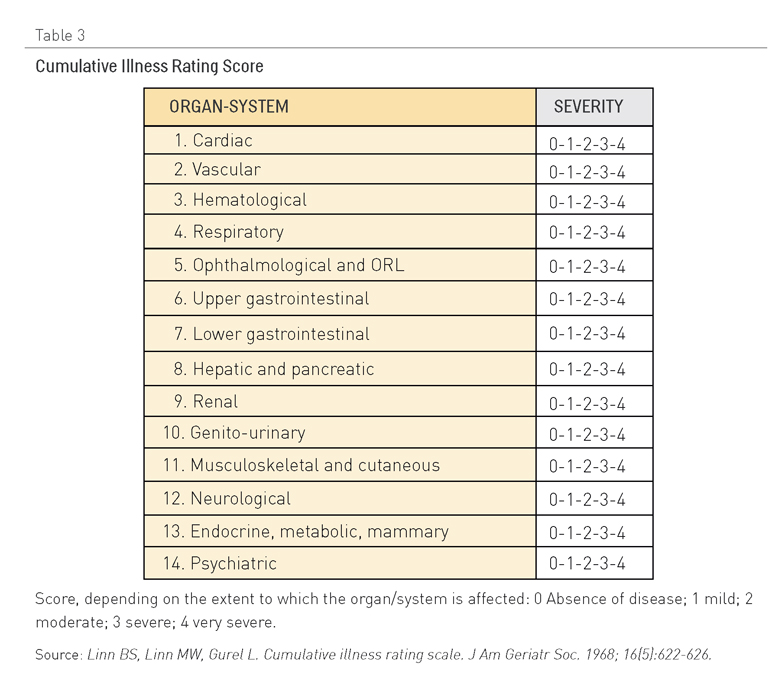

La escala CIRS (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, Escala de valoración acumulativa de enfermedades)

Esta herramienta ha sido validada en diferentes regiones del mundo y en poblaciones de pacientes muy diversas (30). La ventaja principal que ofrece es que su escala de puntuación define en qué medida están afectados órganos y sistemas, sin referirse a enfermedades concretas (Tabla 3). Sin embargo, a pesar de su validez y fiabilidad, hay pocas referencias de su utilización en los estudios de investigación.

Tabla 3: Escala de valoración acumulativa de enfermedades (CIRS)

El ICED (Index of Coexisting Disease, Índice de enfermedades coexistentes)

Este índice se desarrolló (31) como una herramienta para valorar el pronóstico de los supervivientes de cáncer. Posteriormente, se ha validado para otras poblaciones de pacientes con diferentes comorbilidades. La principal ventaja de esta herramienta de pronóstico es que combina dos dimensiones: la gravedad de la enfermedad y el nivel de discapacidad o compromiso funcional tal como lo haya experimentado el paciente.

La primera dimensión (GEI o gravedad de la enfermedad individual) engloba un total de 19 posibles comorbilidades, cada una de las cuales se puntúa sobre una escala que va de 0 (ausencia de la enfermedad en cuestión) a 3 (enfermedad grave).

La segunda dimensión valora el impacto de comorbilidades en estado físico del paciente (DFI o deterioro físico individual). Evalúa once funciones físicas, dándoles una puntuación de 0 (función normal) a 2 (discapacidad grave, dependencia para realizar una función física concreta).

Esta herramienta se utiliza poco, probablemente porque es complicado aplicarla en entornos clínicos con mucho trabajo.

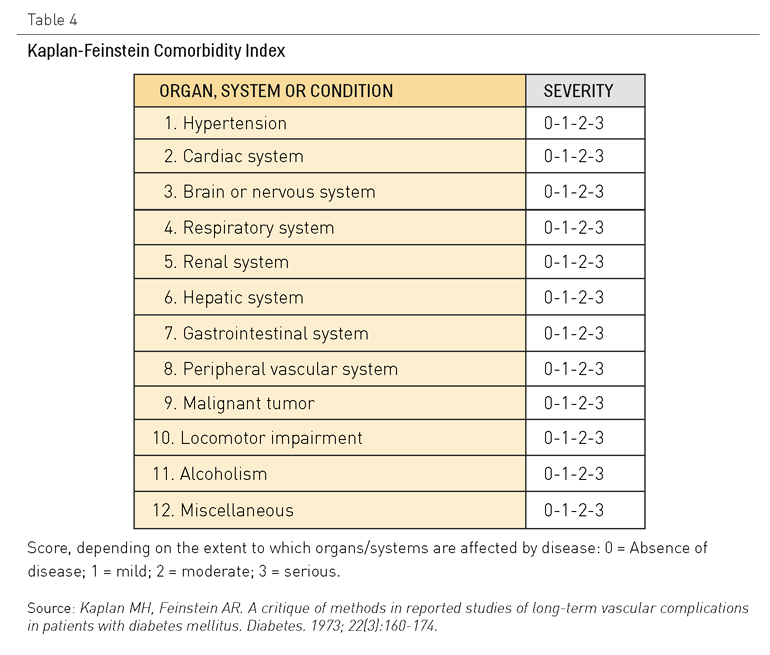

El índice de Kaplan ó de Kaplan-Feinstein

Este índice se desarrolló para facilitar la valoración del pronóstico de pacientes con diabetes en relación con su comorbilidad (32). Posteriormente, se ha intentado exportar este instrumento a otras poblaciones de pacientes, pero los resultados han mostrado muchas divergencias y, por lo tanto, ahora se recomienda utilizarlo solo para la investigación relacionada con la población diabética (Tabla 4).

Tabla 4: Índice de comorbilidad de Kaplan-Feinstein

Otros instrumentos pronósticos

Se ha producido una oleada de actividad desde el inicio de este nuevo siglo, con el desarrollo y la validación de nuevas herramientas a fin de predecir la mortalidad entre los pacientes pluripatológicos mayores de setenta años, principalmente después de recibir el alta hospitalaria (33-36). La Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna apoya también un proyecto multicentro, conocido como PROFUND, que tiene el objetivo de desarrollar una nueva herramienta para la valoración del pronóstico de los pacientes polipatológicos (37).

También se han diseñado otras herramientas para permitir a los pacientes elaborar ellos mismos informes sobre las enfermedades crónicas múltiples (38-40). La utilidad clínica de estos instrumentos aún no está clara.

¿Qué hay que saber?

Las siguientes preguntas tienen el fin de englobar algunas de las lagunas de conocimiento más importantes en relación con el lenguaje de la polipatología:

- ¿Es posible desarrollar una herramienta válida, fácil de usar, que goce de amplia aceptación y centrada en los pacientes que pueda ofrecer una valoración holística de la experiencia de las personas que viven con múltiples enfermedades crónicas? Sería ideal que una herramienta de este tipo (o kit de herramientas) integrara aspectos relacionados con la carga sintomática, el estatus funcional, las necesidades de apoyo psicosocial y la autoevaluación de la salud. También debería adaptarse a los cambios a lo largo del tiempo y resultar útil tanto para médicos (especialmente en entornos clínicos de mucho trabajo), como para investigadores, legisladores, gestores y pacientes.

- ¿Es factible crear un lenguaje común para la polipatología que tenga una aceptación global, una taxonomía? Una iniciativa de este tipo tendría un valor incalculable a la hora de facilitar la codificación y la evaluación de las actividades clínicas, y en la valoración de intervenciones y políticas más allá de las fronteras institucionales y geográficas.

¿Qué estrategias innovadoras podrían acortar las distancias?

El desarrollo y la validación de herramientas útiles y ampliamente aceptadas para identificar, valorar y dirigir la gestión y el estudio de las polipatologías sólo será posible gracias a la colaboración global significativa entre las instituciones académicas, políticas, corporativas y comunitarias más importantes. La plataforma OPIMEC se ha dotado de potentes recursos para que esto sea posible. Incluye un espacio de trabajo dedicado exclusivamente a la creación conjunta de términos relacionados con la polipatología, que se ha rellenado con el contenido extraído de lo que puede que sea aún la única taxonomía diseñada teniendo en mente temas de gestión (41). El espacio también incluye recursos relacionados con los medios sociales que permiten que cualquier persona, desde cualquier lugar del mundo, pueda colaborar y aunar esfuerzos con otras personas con ideas afines, de forma gratuita (42). Ahora, el desafío es utilizar estos recursos con el entusiasmo y el compromiso necesarios para hacer frente al reto.

Contribuyentes

Manuel Ollero, Máximo Bernabeu y Manuel Rincón escribieron el primer borrador de este capítulo en español.

Alejandro Jadad aprobó el primer borrador antes de hacerlo público online a través de la plataforma OPIMEC. Este borrador recibió importantes colaboraciones de Ross Upshur y Bob Berstein (en inglés). Francisco Martos incorporó estas aportaciones a la versión revisada del capítulo, que fue editado en profundidad y aprobado por Alejandro Jadad.

Los principales colaboradores son los responsables del contenido, que no representa necesariamente el punto de vista de la Junta de Andalucía o de cualquier otra institución que haya participado en este esfuerzo conjunto.

Reconocimientos

Antonia Herraiz Mallebrera, José Murcia Zaragoza, Isabel Fernández y Barbara Paterson hicieron comentarios al capítulo (en español) acerca del capítulo que no supusieron cambios en cuanto al contenido.

Cómo citar este capítulo:

Ollero, M.*, Bernabeu, M.*, Rincón, M.*, Upshur, R., Berstein, B. [*Colaboradores principales] EThe language of polypathology. En: Jadad AR, Cabrera A, Martos F, Smith R, Lyons RF. When people live with multiple chronic diseases: a collaborative approach to an emerging global challenge. Granada: Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública; 2010 Disponible en: http://www.opimec.org/equipos/when-people-live-with-multiple-chronic-diseases

Licencia Creative Commons

- Formación en "Mejora en la atención a personas con enfermedades crónicas"

- Mejora en la atención a personas con enfermedades crónicas (2ª edición)

- Mejora en la atención a personas con enfermedades crónicas (1ª edición)

- Plan Andaluz de Atención Integrada a Pacientes con Enfermedades Crónicas (PAAIPEC)

- Cuando las personas viven con múltiples enfermedades crónicas: aproximación colaborativa hacia un reto global emergente