¿Por qué Múltiples Enfermedades Crónicas?¿Por qué ahora? ¿Qué está pasando en todo el mundo?

Este es un documento vivo (más información) titulado "¿Por qué múltiples enfermedades crónicas? ¿Por qué ahora? ¿Qué está pasando en todo el mundo?" y desarrollado en el espacio del equipo Web de trabajo colaborativo en Epidemiología de la polipatología.

Se ha incluido como capítulo 1 en el libro sobre polipatología (índice y PDF del libro; PDF del capítulo en inglés, PDF del capítulo en español).

Puede seguir todos los comentarios aquí o suscribirse a su canal RSS.

Para cualquier comentario, duda, sugerencia o si necesita soporte técnico, por favor no dude en contactar con nosotros en info@opimec.org

A continuación, ¡DISFRUTE del contenido del documento y PARTICIPE en mejorar el conocimiento sobre la polipatología!

Tabla de contenidos

Use el botón “pantalla completa” ![]() para aumentar el tamaño de la ventana y poder editar con mayor comodidad.

para aumentar el tamaño de la ventana y poder editar con mayor comodidad.

En la esquina superior izquierda elija el formato del texto seleccionando en el menú desplegable:

- Párrafo: para texto normal

-Capítulo de primer nivel, de segundo, de tercero: para resaltar los títulos de las secciones y construir el índice. Aquellos enunciados que resalte con este formato aparecerán automáticamente en el índice del documento (tabla de contenidos).

Use las opciones Ctrl V o CMD V para pegar y Ctrl C/CMD C para copiar, Ctrl X/CMD X para cortar (en algunos navegadores no funcionan los botones habilitados para ello)

Al finalizar la edición no olvide guardar los cambios pulsando el botón inferior izquierdo Guardar o Cancelar si no quiere guardar los cambios efectuados

Más información aquí

El precio del éxito

“En este mundo en decadencia, todo lo bueno tiene consecuencias malas no buscadas, todo Yang tiene un Yin" (1).

En 2004, dos académicos anunciaron que habían descubierto la primera versión conocida de un poema de Safo, la poetisa griega conocida como la décima musa (2). Estaba escrito sobre un fragmento de un papiro utilizado para cubrir una momia egipcia conservada en la Universidad de Colonia, en Alemania. El poema, que se había transcrito al menos 300 años tras la muerte de Safo, se convirtió en uno de los ejemplos más completos de su obra de los que se dispone hasta el momento.

El poema es una obra maestra compacta. En solo doce versos, captura las reflexiones de la poetisa sobre su propio proceso de envejecimiento y el sufrimiento de los humanos a medida que envejecemos. Sus palabras, que 2700 años después de escritas suenan más vivas que nunca, dicen así: (las palabras entre corchetes no estaban en el fragmento, fueron añadidas por el traductor (3)):

“[Velad vosotras por] los bellos dones de las Musas ceñidas

de violetas, muchachas, [y por la] dulce lira de los cantos,

[pero] mi piel, [en otro tiempo suave], de la vejez ya [es presa],

y tengo [blancos] mis cabellos que fueron negros,

y torpes se han vuelto mis fuerzas, y las piernas no me sostienen,

antaño ágiles cual cervatillos para la danza.

He aquí mis asiduos lamentos, pero ¿qué podría hacer yo?

A un ser humano no le es dado durar por siempre.

A Titono, una vez, cuentan que Aurora de rosados brazos

por obra de amor lo condujo a los confines de la Tierra,

joven y hermoso como era, mas lo encontró igualmente al cabo

la canosa vejez, a él, que tenía esposa inmortal.”

En las últimas cuatro líneas Safo se refiere a un mito que fue muy popular en el siglo VII a.C. como medio para expresar el sufrimiento asociado al deterioro del cuerpo humano a medida que pasan los años.

Según esta historia, la diosa del amanecer, Eos (Aurora para los romanos), se había enamorado de Titono, un troyano. Como no podía concebir la vida sin su amante mortal, Eos convenció a Zeus para que concediera a Titono la vida eterna. Sin embargo, Zeus interpretó la petición de Eos de forma literal: convirtió a Titono en inmortal, pero no le concedió el don de la eterna juventud. En consecuencia, Titono empezó a envejecer, se debilitó progresivamente a causa de múltiples enfermedades crónicas y perdió la cordura. El mito finaliza con Eos transformando a Titono en una cigarra para mitigar su sufrimiento.

En los albores del siglo XXI, millones de personas en todo el mundo se enfrentan a los mismos retos ilustrados en el mito de Titono y en el poema de Safo. El extraordinario nivel de control de las enfermedades agudas y la consiguiente prolongación de la esperanza de vida que hemos alcanzado los humanos en el siglo XX lleva ahora a una epidemia global de enfermedades y dolencias crónicas.

La elevada prevalencia de las enfermedades crónicas ya está teniendo un efecto importante en los datos de mortalidad en todo el mundo. En un informe sin precedentes titulado Prevención de las enfermedades crónicas: una inversión vital, la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) calculó que el 60% de las muertes ocurridas en todo el mundo en 2005 ya se debía a enfermedades crónicas, y el 80% del total se produjo en países de renta baja a renta media (4). De hecho, las enfermedades crónicas son la principal causa de mortandad en todos los países del mundo, excepto en los que tienen los niveles de renta más bajos. Sin embargo, incluso en estos países la distancia entre las enfermedades crónicas y las infecciosas cada vez es menor (5). Para agravar esta situación, la depresión, y no las heridas físicas, constituye en la actualidad la principal causa de años perdidos por incapacidad en todo el mundo (6).

Desgraciadamente, esta epidemia, que ha sido el objeto de muchos estudios recientes (7), se subestima e incluso se ignora (8).

El surgimiento de la polipatología

La elevada prevalencia de enfermedades crónicas ya ha dado lugar a un fenómeno nuevo: cada vez es mayor el número de personas que viven con múltiples enfermedades crónicas.

Este fenómeno no incluye sólo a las personas con una enfermedad primaria que desencadena enfermedades secundarias (por ejemplo, una persona con diabetes que sufre retinopatía y neuropatía asociadas), sino también a aquellas en las que coexisten dos o más enfermedades (por ejemplo, personas con diabetes, cáncer y enfermedad de Alzheimer al mismo tiempo).

No obstante, como ocurre con los fragmentos de los poemas de Safo, el conocimiento acerca de la prevalencia y de la carga social de la polipatología para los diferentes grupos de edad, a un nivel global, es muy incompleto. La mayoría de informes ofrecen datos sobre grupos de enfermedades concretos, en grupos de alto riesgo, o en regiones o países específicos (9). Son muy pocos, si es que los hay, los que contienen datos originales acerca de la prevalencia de varias enfermedades, detectadas y documentadas simultáneamente, en todos los grupos de edad, en todo el mundo.

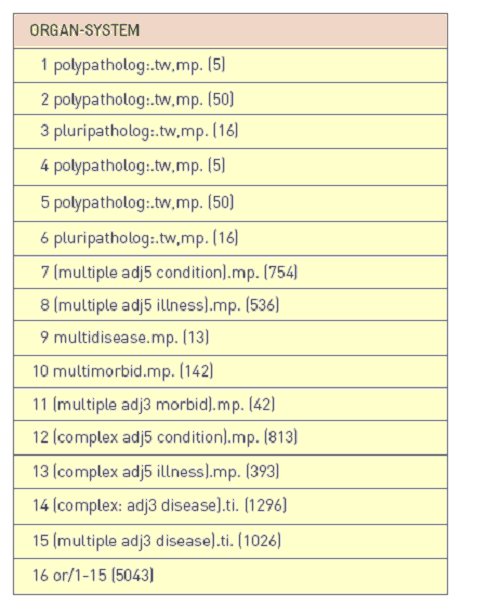

Una búsqueda avanzada en MEDLINE realizada el 14 de abril de 2009 (figura 1), complementada por una búsqueda en Google y en Google Académico el 22 de agosto de 2009, dejó entrever lo que puede estar pasando en términos de la prevalencia de la polipatología.

Figura 1. Estrategia de búsqueda

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1950 to April Week 1 2009>.

Fuente: U.S. National Library of Medicine. Ovid Medline [Web site]. [ Acceso 1 Abril 2009]. Disponible en:http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com/

Uno de los mensajes principales de la bibliografía fragmentaria existente es que las estimaciones de la prevalencia de la polipatología entre los miembros adultos del público general varían en gran medida, con cifras que van del 17% a más del 50% (10,13).

Un hallazgo más consistente es que las personas que sufren polipatología pueden representar el 50% o más de la población que vive con enfermedades crónicas, al menos en los países de rentas altas. Por ejemplo, una revisión sistemática de 25 estudios australianos realizados entre 1996 y 2007 reveló que la mitad de los pacientes ancianos incluidos con artritis también tenía hipertensión, el 20% tenían enfermedad cardiovascular (ECV), el 14% diabetes y el 12%, problemas de salud mental. De forma similar, más del 60% de los pacientes con asma informaron que también sufrían artritis, el 20% ECV, y el 16%, diabetes; y entre los que padecían ECV, el 60% también tenía artritis, el 20%, diabetes y el 10% tenía asma o problemas de salud mental (14). El estudio de una muestra aleatoria de 1.217.103 pacientes de Estados Unidos que habían recibido servicios de Medicare durante más de un año (es decir, que tenían 65 años o más), mostró que dos tercios (65%) padecían múltiples enfermedades crónicas(15). Los estudios de pacientes admitidos en hospitales en España también muestran una prevalencia de polipatología que va del 42% a poco más del 57% (16,17).

Los datos procedentes de otros estudios muestran unos niveles de prevalencia aún más elevados entre las personas que conviven con enfermedades crónicas específicas. El análisis de cinco ensayos clínicos en pacientes con hipertensión en Canadá seleccionados al azar en 2003 mostró que del 89% al 100% tenían múltiples enfermedades crónicas, con un media de afecciones crónicas que oscilaba entre 5 y 12 (18). Un patrón similar se encontró entre las personas afectadas por enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC) como enfermedad primaria en Italia, donde al 98% de los participantes en una gran cohorte de pacientes se les había recetado al menos un fármaco no específico para el sistema respiratorio. La enfermedad coexistente era de tipo cardiovascular en el 64% de los casos, diabetes en el 12% y depresión en el 8% (19). También se halló una prevalencia de polipatología del 91% en una muestra de pacientes indigentes, predominantemente afroamericanos, en Estados Unidos (20).

Como se esperaba, la prevalencia de polipatología parece aumentar con la edad. Una valoración de dos grandes encuestas llevadas a cabo en Australia a nivel nacional en 2001 y 2003 mostró que la proporción de personas que vivían con tres o más enfermedades crónicas aumentaba del 34% para los miembros del público general con edades comprendidas entre 20 y 39 años, al 57% entre los que tenían entre 40 y 59 años, hasta llegar al 80% para las personas de entre 60 y 74 años, y al 86% a los 75 años o más (12).

Resulta difícil determinar la proporción de personas que padecen un número diferente de enfermedades coexistentes no solo por la escasez de estudios, sino debido al uso de diferentes criterios de medida empleados en los estudios existentes. En Dinamarca, el análisis de los datos obtenidos a lo largo de dos décadas indicó que en el 7% de las personas con edades comprendidas entre 45 y 64 años estaban presentes cuatro o más enfermedades, porcentaje que aumentaba hasta el 30% para aquellos de entre 65 y 74 años, y hasta el 55% entre los mayores de 75 años (21). Los análisis de los beneficiarios de Medicare han mostrado que el 23% de ellos vive con cinco o más enfermedades (22). En España, se calculaba que las personas con edades comprendidas entre 65 y 74 años tenían un promedio de 2,8 enfermedades crónicas, mientras que los mayores de 75 tenían 3,2 (23). Un estudio francés de 100 pacientes de 80 años o más que se encontraban hospitalizados en una unidad geriátrica mostró que el promedio de enfermedades reconocidas por paciente era de 4,1 (24).

Además de la edad avanzada, análisis multivariados han demostrado que la obesidad, el hecho de ser mujer con un status socioeconómico bajo, y vivir solo son factores que aumentan de manera significativa la probabilidad de tener tres o más enfermedades crónicas (12).

Aparte de la relación con el género y la edad avanzada, otro estudio indicó que existía un mayor riesgo de polipatología entre las personas con un nivel de educación bajo, las que tienen seguro médico público y las que viven en una residencia de ancianos (10).

Los datos de los que se dispone en relación con las tasas de mortalidad causada por varias enfermedades crónicas en personas con polipatología también son limitados. Un estudio de individuos de entre 55 y 64 años que hicieron uso de los servicios sanitarios de la Veterans Health Administration entre octubre de 1999 y septiembre de 2000 mostró una tasa de mortalidad de 5 años que aumentaba del 8% entre las personas con dos enfermedades, al 11% entre las que padecían tres, hasta llegar al 17% entre las que tenían cuatro o más (25).

Los datos acerca de la polipatología en países de renta baja o media también son dispersos. En un estudio de 844 pacientes de un hospital en Soweto, Sudáfrica, que padecían insuficiencia cardiaca, 172 (24%) presentaban también disfunción renal, 83 (10%), enfermedad coronaria, 18 (2%), un historial de infarto agudo de miocardio, 86 (10%), diabetes, 72 (10%), anemia, 58 (7%), infarto cerebral, y 53 (6%), fibrilación auricular (26). Una encuesta de hogares afectados de forma importante por enfermedades graves en dos provincias de China identificó a 2.259 personas con enfermedades crónicas, de las cuales 2.140 (95%) padecían una enfermedad, 110 (5%), dos, y 9 (0,4%), tres (comunicación personal) (27).

Solo uno de los estudios identificados proporcionó datos acerca de la prevalencia entre niños o adolescentes. Este informe, para el que se utilizaron datos procedentes de la Red de Registro de Médicos de Familia de los Países Bajos, mostraba que el 10% de las personas desde el nacimiento hasta la edad de 19 años tiene probabilidad de tener múltiples enfermedades crónicas (10).

¿Por qué este libro ahora?

Nuestro limitado conocimiento acerca de la polipatología no se limita solo a la comprensión de su prevalencia. En 2006, la Veterans Health Administration organizó un congreso con el título “Gestionar la complejidad en el cuidado de enfermedades crónicas”, motivado por el riesgo de que los fondos para hacer frente a las necesidades sanitarias de su población objetivo (veteranos de guerra, miembros en servicio activo en tiempo de guerra y personas víctimas de emergencias nacionales) fueran insuficientes. Esta preocupación se vio impulsada por la constatación de que el 96% del gasto de Medicare en ese momento ya se destinaba a personas con múltiples enfermedades crónicas (28).

El congreso, que pretendía “clarificar nuestra comprensión actual de la gestión de enfermedades crónicas complejas y dar indicaciones para la investigación con el fin de mejorar la gestión de este problema tan importante”, reunió a expertos de dentro y fuera de Estados Unidos que habían elaborado y revisado publicaciones acerca de algunos de los aspectos clave de la gestión de las enfermedades crónicas complejas. Basándose en esas interacciones preliminares, el congreso se centró en seis puntos:

- identificar a los pacientes con enfermedades crónicas complejas,

- planificar la gestión de la propia enfermedad por parte de pacientes con enfermedades crónicas complejas,

- desarrollar la evidencia y la base de conocimiento para gestionar pacientes con enfermedades crónicas complejas,

- mejorar los sistemas de gestión de la atención a pacientes con enfermedades crónicas complejas,

utilizar la informática para la atención de pacientes con enfermedades crónicas complejas, y - establecer un vínculo entre el paciente y las estrategias del sistema para la gestión de la complejidad.

Las reflexiones generadas antes, durante y después de este importante encuentro se publicaron en forma de nueve artículos breves en un suplemento especial del Journal of General Internal Medicine en diciembre de 2007 (29). En un resumen general que se publicó a la vez se enumeraban nueve temas clave de investigación que se habían identificado como resultado de las deliberaciones de los participantes acerca de las necesidades no satisfechas de las personas que sufren enfermedades crónicas múltiples (figura 2).

Figura 2. Temas de Investigación en la gestión de las necesidades de atención de pacientes con enfermedades crónicas complejas identificadas en el congreso patrocinado por la Veterans Health Administration en 2006 (28)

1. Describir cohortes de pacientes de alto riesgo con múltiples enfermedades crónicas (MEC) y complejidad social, incluyendo su impacto en los servicios sanitarios. A partir de este trabajo, desarrollar una lista de prioridades de las MEC y la complejidad social para intervenciones orientadas al objetivo.

2. Sintetizar/Analizar sistemáticamente la bibliografía acerca de las intervenciones relacionadas con la polipatología y las necesidades médicas complejas de pacientes con complejidad social.

3. Avanzar el trabajo en cuanto a la valoración de resultados, incluyendo medidas de atención integral y resultados optimizados para pacientes con polipatología.

4. Aumentar el número de estudios acerca de la eficacia y la efectividad basados en la evidencia para apoyar las directrices que se adaptan a las polipatologías y a la complejidad social para pacientes complejos de prioridad alta.

5. Desarrollar medidas de rendimiento más óptimas que reflejen la morbilidad compleja, incluyendo las que se centren en la autogestión del paciente y en la coordinación de la asistencia médica.

6. Evaluar los cambios en los sistemas que organizan la asistencia en torno a las polipatologías y la complejidad social de la gestión de las enfermedades, como son:

- nuevas estrategias basadas en el equipo para la asistencia sanitaria en la gestión de la asistencia a pacientes con polipatología

- el nuevo papel, cada vez más importante en la asistencia, de los miembros no médicos del equipo

- el papel y los diferentes diseños de un entorno médico preventivo para gestionar pacientes con necesidades de asistencia complejas

- la importancia de compartir la asistencia entre las especialidades médicas y las líneas de servicio para conseguir una óptima gestión de la atención sanitaria

- apoyo a la autogestión, incluyendo estructuras de aprendizaje en grupo

- sistemas de asistencia de alto rendimiento para el cuidado de pacientes con polipatología de alta prioridad

- asistencia tecnológica para pacientes con deficiencias visuales, auditivas o físicas de otro tipo para optimizar la gestión de la asistencia compleja.

7. Examinar las mejores prácticas en las estrategias de comunicación entre paciente y médico para tomar decisiones respecto a la gestión de la atención médica en casos de pacientes con MEC o con complejidad social. Este punto enfatizó estrategias para conocer las preferencias del paciente ante la complejidad de la asistencia y para implicar a las estructuras sociales de apoyo (por ejemplo, la familia)

8. Valorar las nuevas estrategias de la tecnología de la información aplicadas a la salud para apoyar la gestión de la asistencia sanitaria compleja con el fin de avanzar en los conocimientos que se tienen en relación con los siguientes aspectos:

- ¿Qué herramientas de apoyo a las decisiones se necesitan en el caso de pacientes con necesidades de asistencia médica compleja?

- ¿De qué modo pueden los registros de pacientes apoyar mejor la gestión de la asistencia para pacientes con MEC?

- ¿Qué tipo de herramientas de las tecnologías de la información aplicadas a la salud se pueden desarrollar para optimizar la autogestión de los pacientes?

9. Identificar las mejores prácticas para integrar los servicios de rehabilitación en las estrategias de gestión del paciente para pacientes con necesidades de asistencia médica crónica compleja.

Sin tener conciencia de estos esfuerzos, dirigentes de la Consejería de Salud de Andalucía, en España, también constataron un incremento en la prevalencia y la carga de las enfermedades crónicas complejas entre su población objetivo, y lo convirtieron en una de sus mayores prioridades de actuación. Dado que habían prestado su apoyo a un esfuerzo de colaboración a largo plazo para desarrollar, implementar y evaluar un proceso de asistencia con el fin de optimizar la gestión de la polipatología en todos los niveles de su sistema sanitario regional, tenían pleno conocimiento del lento crecimiento del interés por este tema en otras partes del mundo. También eran conscientes de la falta casi total de colaboración significativa entre los principales grupos que estaban trabajando en esta área. Constataron que la mayor parte del trabajo disponible se había desarrollado en focos aislados, con lo cual se habían perdido oportunidades importantes de llevar a cabo un aprendizaje colectivo efectivo y de crear un esfuerzo conjunto a gran escala, aspectos imprescindibles para hacer frente a las necesidades de las personas que sufren múltiples enfermedades crónicas.

En 2006 no existía ni un solo sitio, físico o digital, en el que las personas interesadas en este tema pudiesen colaborar traspasando las tradicionales fronteras institucionales, geográficas, profesionales, lingüísticas, políticas, disciplinarias y culturales con el fin de de afrontar los retos creados por la polipatología.

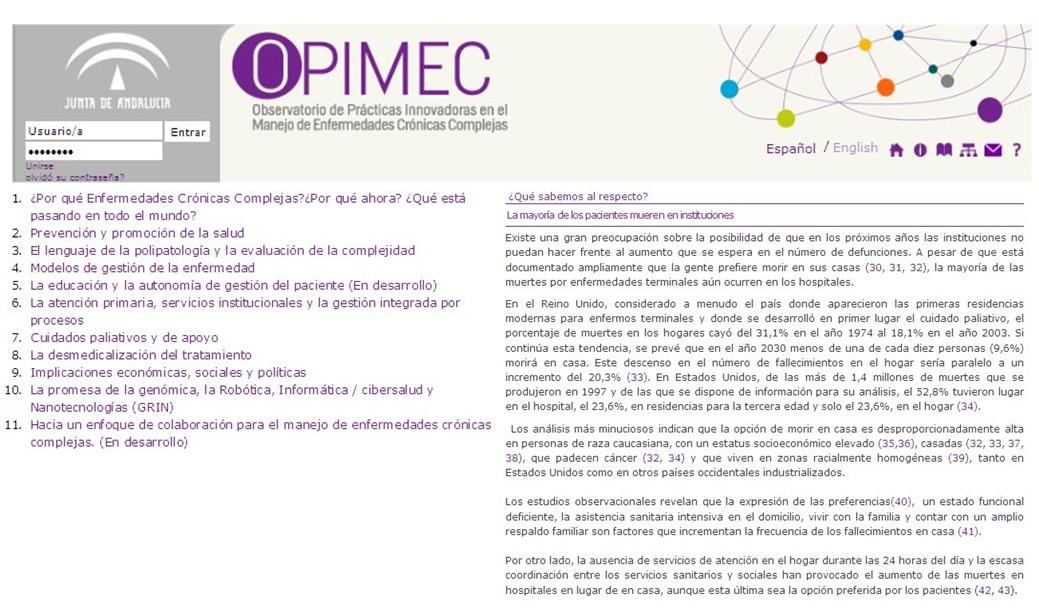

Ante este panorama, y animados por el rápido desarrollo y penetración de potentes recursos online de colaboración (como los wikis o las redes sociales), la Consejería de Salud de Andalucía decidió promover la creación de un observatorio global diseñado para fomentar el intercambio de conocimiento y los esfuerzos conjuntos entre personas e instituciones interesadas en la gestión de las enfermedades crónicas complejas, en cualquier parte del mundo.

El Observatorio, conocido como OPIMEC (Observatorio de Prácticas Innovadoras en el Manejo de Enfermedades Crónicas Complejas), está disponible en inglés y en español en www.opimec.org. Básicamente, se trata de un entorno virtual de colaboración que utiliza herramientas de comunicación de última generación para permitir a los profesionales de la salud, investigadores, legisladores y al público general lo siguiente:

- acceder y contribuir al desarrollo de un lenguaje común con el que mejorar la comunicación acerca de las enfermedades crónicas complejas venciendo las barreras tradicionales (con la ayuda de wikis);

- identificar, clasificar, sugerir y adoptar prácticas innovadoras que podrían mejorar la calidad de la atención sanitaria en sus propios centros de atención (con la ayuda de mapas interactivos), y

- comunicarse y colaborar con personas que comparten un interés por afrontar los retos relacionados con las enfermedades crónicas complejas (con la ayuda de las redes sociales online).

En marzo de 2009, la Consejería organizó un encuentro en Sevilla al que asistieron sus principales responsables de la gestión de la polipatología a nivel regional, así como también sus colaboradores más cercanos de otras regiones de España y de todo el mundo. Juntos, los participantes identificaron nueve aspectos poco comprendidos relacionados con polipatología que podrían beneficiarse de iniciativas de colaboración internacionales:

- aspectos epidemiológicos,

- prevención y fomento de la salud,

- el lenguaje de la polipatología y valoración de la complejidad,

- modelos de gestión de la enfermedad,

- educación del paciente y gestión de la propia enfermedad,

- atención primaria y procesos de gestión integrados,

- cuidado de apoyo y paliativo,

- desmedicalización del tratamiento (poniendo especial atención en las intervenciones complementarias y alternativas, y la Medicina Integral),

- implicaciones económicas, sociales y políticas,

- la promesa de la genómica, la robótica, la informática/eSalud y las nanotecnologías (GRIN).

Colectivamente, los participantes en el evento expresaron un gran interés en la utilización de OPIMEC para desarrollar conjuntamente y compartir un compendio de conocimientos en constante evolución que pudiera estar al alcance de cualquiera, en cualquier parte del mundo, en todo momento, en formato digital y de forma gratuita. Como catalizador de este ambicioso proyecto de colaboración global, el grupo decidió publicar un libro, en formato digital y en papel, en inglés y en español, que pudiera lanzarse al público durante la presidencia española de la Unión Europea en la primera mitad de 2010.

El enfoque

Durante el congreso celebrado en marzo de 2009, se invitó a los participantes a ser contribuyentes principales o a sugerir posibles contribuyentes para capítulos concretos del libro centrados en cada uno de los aspectos que se habían identificado como poco comprendidos y a menudo ignorados acerca de este tema.

A finales de mes, todos los capítulos se habían asignado a un contribuyente principal, que se había comprometido a tener la primera versión lista para verano de 2009. En ese momento, también se había confirmado el grupo editorial principal inicial (la Dra. Lyons se unió al grupo editorial a finales de ese año) y se había constituido un equipo para dar soporte técnico a los editores y a los contribuyentes.

Todos los contribuyentes principales se pusieron de acuerdo para seguir una serie de principios para garantizar la máxima transparencia al público futuro y para evitar percepciones innecesarias de conflictos de interés o de opinión sesgada. Los contribuyentes se comprometieron a:

- utilizar un lenguaje que pudiera ser accesible a los diferentes públicos potenciales, incluidos legisladores, medios, gestores e investigadores. Un resumen para no expertos recogería la información esencial de cada capítulo de forma que la público general le fuera fácil entender las ideas básicas;

- declarar su afiliación a instituciones que pudieran tener un interés en la gestión de las ECC en general, o en un aspecto en concreto;

- declarar explícitamente cualquier inclinación personal o institucional que pudiera influir en el tono adoptado al tratar el tema en cuestión y el énfasis que se le diera;

- evitar poner un énfasis excesivo o centrarse solo en aspectos relacionados con sus actividades profesionales o con sus objetivos institucionales, ya fueran de carácter político, económico o académico;

- reconocer, siempre que fuera posible, el trabajo de personas e instituciones con puntos de vista opuestos o con intereses que entraran en competencia con los suyos, y

- aportar sus contribuciones sin contar con incentivos económicos o políticos.

Los contribuyentes acordaron también seguir un formato estructurado para cada uno de los capítulos, con los apartados siguientes:

- un breve esbozo, o viñeta, perfilando una visión del futuro con un horizonte de 20 a 30 años.

- un pequeño resumen para destacar los principales puntos tratados en el resto del capítulo, empleando un lenguaje que pueda comprender cualquier lector interesado en el tema.

- ¿Por qué es importante este tema? En este apartado se describe la magnitud del reto en relación con este tema concreto, ofreciendo tantos datos como sea posible, incluyendo todas las regiones de mundo e intentando recoger las perspectivas de los diferentes grupos de sectores interesados (los pacientes y sus cuidadores, los legisladores, los gestores, los patrocinadores y los académicos).

- ¿Qué sabemos? Aquí, los contribuyentes resumen la bibliografía disponible sobre el tema, destacando las implicaciones para cada uno de los diferentes grupos interesados mencionados en el apartado anterior. En cada capítulo, los contribuyentes aseguran que han recurrido tanto a la bibliografía inicial como a sus propias recopilaciones de recursos.

- ¿Qué hay que saber? En este apartado se destacan las brechas de conocimiento que existen acerca de este tema, y por qué sería importante rellenarlas.

- ¿Qué estrategias innovadoras podrían acortar las distancias? Los contribuyentes finalizan todos los capítulos con propuestas innovadoras de esfuerzos que se podrían llevar a cabo para rellenar las brechas identificadas, centrándose en aspectos metodológicos, en las necesidades de recursos (tecnológicos, financieros y humanos) y en el papel que el OPIMEC podría desempeñar en el proceso.

Seis de los capítulos se redactaron inicialmente en español y cuatro en inglés (los que trataban de aspectos epidemiológicos, prevención y promoción de la salud, cuidados paliativos y de apoyo, y demedicalización del tratamiento).

Uno de los editores principales (FM) ayudó a los contribuyentes que escribían en español y otro (ARJ), a los que lo hacían en inglés. Este último, que domina ambas lenguas, fue el responsable de revisar todas las versiones iniciales con el fin de armonizar el contenido, eliminar la información redundante e identificar puntos que se podrían mejorar.

Las primeras versiones revisadas de los capítulos, con las modificaciones sugeridas, se enviaron a cada uno de los contribuyentes principales quienes, a su vez, redactaron versiones mejoradas. En la mayoría de casos, las versiones iniciales se revisaron dos veces antes de considerar que estaban listas para ser traducidas.

Una vez que las versiones se tradujeron a la otra lengua, el mismo editor bilingüe (ARJ) las revisó para asegurarse de que fueran exactas y, en los casos necesarios, editó aún más el contenido en ambas lenguas.

Los archivos traducidos se enviaron a los respectivos contribuyentes principales para que los verificaran y aprobaran. Una vez aprobados, el equipo de soporte técnico subió los capítulos redactados a la plataforma del OPIMEC en un formato que presentaba apartados interactivos separados diseñados para permitir a los lectores hacer comentarios y sugerencias para mejorarlos (figura 3).

Figura 3. Tabla interactiva de contenidos con una muestra de un apartado

Mientras los capítulos se subían a la plataforma, los contribuyentes y los editores elaboraron una lista de expertos que consideraban que podían aportar comentarios útiles sobre cada uno de los capítulos, seleccionándolos de entre los colegas que conocían o entre los autores de los artículos clave que habían utilizado como referencia. Entonces, los editores enviaron un mensaje electrónico a los miembros de esa lista invitándolos a leer los capítulos y a hacer comentarios, bien de forma anónima, bien registrándose como miembros de la comunidad OPIMEC. En todos los casos, el equipo de soporte se mostró dispuesto a ofrecer la asistencia técnica necesaria bajo la supervisión de uno de los editores (AC).

A lo largo del proceso, los términos “contribuyente” y “contribución” se consideraron más coherentes con los enfoques modernos que reconocen la labor de miembros de grupos de contribuyentes que los más tradicionales “autor” o “autoría” (30)

Transcurrido como mínimo un mes desde que los capítulos se subieron a la plataforma, los editores revisaron todos los comentarios recibidos y elaboraron listas de modificaciones significativas que se enviaron a los contribuyentes principales para que se incorporaran a los textos.

A continuación, los editores (RS, RL y ARJ en inglés, y PM, AC y ARJ en español) volvieron a analizar a fondo las versiones revisadas e introdujeron online las modificaciones necesarias del texto principal. Las personas que habían hecho comentarios esenciales, con el consenso de los editores, se reconocieron como contribuyentes del libro.

El resultado

A finales de febrero de 2010, menos de un año después de haberse celebrado el congreso original en Sevilla, los diez capítulos que presentamos en este libro se habían terminado, se habían revisado en borrador como mínimo dos veces y habían sido aprobados por los editores. El capítulo once se añadió poco antes de la entrega de la versión definitiva de la edición en papel del libro en el mes de abril de 2010.

Se recibieron colaboraciones de personas de todos los continentes habitados. Sin embargo, la mayoría de las colaboraciones las hicieron principalmente personas con las que los editores se pusieron en contacto al principio del proyecto y miembros de sus equipos cercanos o círculos de contribuyentes.

A pesar de la facilidad de uso y de la disponibilidad de soporte técnico en todo momento, los contribuyentes han preferido utilizar el correo electrónico tradicional para producir contenido antes que hacer uso de los recursos disponibles online en la plataforma del OPIMEC. Esto ha dificultado en ocasiones el proceso de edición, ya que los contribuyentes enviaban diferentes versiones de su trabajo directamente a cada editor, con lo que se creaba una confusión innecesaria y suponía duplicar esfuerzos.

Por otra parte, los editores se comunicaban principalmente por correo electrónico y completaban sus frecuentes interacciones (como mínimo semanales) en forma de texto con videoconferencias online y encuentros cara a cara, siempre que fuera posible.

Convertir las colaboraciones en versiones homogéneas en inglés y español no fue un proceso sencillo. Las traducciones, que eran en su mayor parte el reflejo exacto de los textos originales, han precisado de mucha edición para hacer que los lectores de la otra lengua los puedan leer de la forma más cómoda posible, lo cual ha provocado desajustes inevitables entre las versiones, que podrán identificar fácilmente los lectores bilingües en la mayoría de casos.

Otro aspecto interesante de este esfuerzo fue el proceso de decidir cuándo considerar que el contenido digital generado por un conjunto tan diverso de contribuyentes estaba listo para su publicación en forma de libro. En la mayoría de casos, el umbral quedaba determinado por la ausencia de comentarios de nuevos contribuyentes o de contribuyentes ya existentes. En los pocos restantes, los editores tuvieron que decidir, por consenso, que el capítulo ya era suficientemente bueno para publicarlo en forma estática. No era posible continuar revisando estos pocos capítulos debido a las limitaciones impuestas por los plazos editoriales y la necesidad de lanzar al mercado el contenido en forma de libro en papel a principios de junio de 2010. No obstante, el hecho de poder tener todos los contenidos disponibles online a través de la plataforma OPIMEC debería permitir a cualquier lector interesado en el tema hacer sugerencias acerca de cómo mejorar lo que se ha hecho hasta el momento. No obstante, el hecho de poder tener todos los contenidos disponibles online a través de la plataforma OPIMEC debería permitir a cualquier lector interesado en el tema hacer sugerencias acerca de cómo mejorar lo que se ha hecho hasta el momento.

En cualquier caso, el libro ha alcanzado su objetivo global original: actuar como un poderoso estímulo para el esfuerzo colectivo, rompiendo las fronteras tradicionales entre personas interesadas en mejorar la gestión de las enfermedades crónicas multiples. Sin el aliciente relacionado con la creación de algo tan tangible o la presión generada por los plazos de publicación y de lanzamiento habría sido difícil conseguir tanto, en un período de tiempo tan breve, y sin incentivos económicos. Por el camino, las personas que respondieron han hecho un esfuerzo considerable y generoso para resumir el limitado conocimiento del que se dispone acerca de este tema tan importante y tantas veces olvidado, y han propuesto, al mismo tiempo, estrategias innovadoras para acortar la distancia existente entre lo que se sabe y lo que se debería hacer para atender las necesidades y las expectativas de un número de personas cada vez más vulnerable y creciente en todas las sociedades del mundo.

Contribuyentes

Alejandro Jadad (AJ) escribió la primera versión de este capítulo en inglés y aprobó su traducción al español. El resto de editores (Andrés Cabrera, Francisco Martos, Renée Lyons y Richard Smith) revisaron el capítulo y lo aprobaron, con algunos comentarios mínimos. AJ incorporó estos comentarios, junto con las valiosas contribuciones de Kerry Kuluski, a la versión final que se incluyó en la versión en papel del libro.

Los contribuyentes son los responsables del contenido, que no representa necesariamente el punto de vista de la Junta de Andalucía o de cualquier otra institución que haya participado en este esfuerzo conjunto.

Agradecimientos

Joseph Ana, Jose Miguel Morales Asencio, Bob Bernstein, Murray Enkin, John Gilles, Marina Gomez-Arcas, Rodrigo Gutierrez, Jacqueline Ponzo y Ross Upshur aportaron interesantes comentarios acerca del capítulo que no supusieron cambios en cuanto al contenido. Esos comentarios, muy apreciados por los editores, se tuvieron en cuenta para incluirlos en otros capítulos del libro.

Cómo citar este capítulo

Jadad AR, Cabrera A, Martos F, Smith R, Lyons RF. Why Multiple Chronic Diseases? Why now? What is going on around the world?. En: Jadad AR, Cabrera A, Martos F, Smith R, Lyons RF. When people live with multiple chronic diseases: a collaborative approach to an emerging global challenge. Granada: Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública; 2010. Disponible en:http://www.opimec.org/equipos/when-people-live-with-multiple-chronic-diseases

Licencia Creative Commons

¿Por qué Enfermedades Crónicas Complejas?¿Por qué ahora? ¿Qué está pasando en todo el mundo? por Jadad AR, Cabrera A, Martos F, Lyons RF y Smith R está bajo licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 3.0 España License.