Modelos de gestión

Este es un documento vivo (más información) titulado "Modelos de gestión" y desarrollado en el espacio del equipo Web de trabajo colaborativo en modelos de gestión de la enfermedad.

Se ha incluido como capítulo 4 en el libro sobre polipatología (índice y PDF del libro; PDF del capítulo en inglés, PDF del capítulo en español).

El ejercicio relacionado con el curso consiste en realizar comentarios a las secciones a través del bocadillo que aparece en la esquina superior derecha de cada sección.

Puede seguir todos los comentarios aquí o suscribirse a su canal RSS.

Para cualquier comentario, duda, sugerencia o si necesita soporte técnico, por favor no dude en contactar con nosotros en info@opimec.org

A continuación, ¡DISFRUTE del contenido del documento y PARTICIPE en mejorar el conocimiento sobre la polipatología!

Tabla de contenidos

- Viñeta: Cómo podría ser

- Resumen

- ¿Por qué es este tema importante?

- ¿Qué sabemos?

- Modelos genéricos de gestión de enfermedades crónicas

- CCM y enfermedades crónicas múltiples

- Estratificación de riesgos y gestión de casos

- ¿Qué hay que saber?

- ¿Qué estrategias innovadoras podrían acortar las distancias?

- Contribuyentes

- Referencias bibliográficas (pulse aquí para acceder)

- Licencia Creative Commons

Use el botón “pantalla completa” ![]() para aumentar el tamaño de la ventana y poder editar con mayor comodidad.

para aumentar el tamaño de la ventana y poder editar con mayor comodidad.

En la esquina superior izquierda elija el formato del texto seleccionando en el menú desplegable:

- Párrafo: para texto normal

-Capítulo de primer nivel, de segundo, de tercero: para resaltar los títulos de las secciones y construir el índice. Aquellos enunciados que resalte con este formato aparecerán automáticamente en el índice del documento (tabla de contenidos).

Use las opciones Ctrl V o CMD V para pegar y Ctrl C/CMD C para copiar, Ctrl X/CMD X para cortar (en algunos navegadores no funcionan los botones habilitados para ello)

Al finalizar la edición no olvide guardar los cambios pulsando el botón inferior izquierdo Guardar o Cancelar si no quiere guardar los cambios efectuados

Más información aquí

Viñeta: Cómo podría ser

La enfermera encargada de la gestión de casos en el centro de salud se puso en contacto con la médica del hospital, para ponerle al corriente de la evolución de un paciente anciano, el Sr. Smith. Éste había recibido el alta hospitalaria una semana antes, después de haber ingresado por un episodio agudo de insuficiencia cardíaca crónica, que había complicado su diabetes, hipertensión e insuficiencia renal crónica. Era uno de los 3 pacientes con el mismo diagnóstico que estaban siendo tratados a la vez por la enfermera. El contacto con la médica del hospital era fundamental para ajustar la medicación que sus pacientes necesitaban y evitar nuevos ingresos hospitalarios. No había ninguna guía de práctica clínica que se adecuase a estos pacientes, puesto que todos ellos sufrían múltiples enfermedades y numerosas necesidades. Desde el inicio del programa de gestión de casos de insuficiencia cardíaca para pacientes con repetidos ingresos, la tasa anual de reingresos había bajado un 40% cada año y se habían logrado grandes niveles de satisfacción, tanto entre los pacientes como entre sus familias. La enfermera encargada de la gestión de casos había desempeñado un papel fundamental en el programa, con labores que iban desde ocuparse de la formación inicial del paciente en su autocuidado, hasta comprobar que se seguía el tratamiento, y encargarse del apoyo a la asistencia en el hogar en aquellos casos donde era necesario. Todo el sistema funcionaba como una unidad bien orquestada, gracias a una avanzada infraestructura de información y comunicación, que no sólo permitía una interacción fluida entre el cuidado hospitalario y ambulatorio, sino que también tomaba en consideración las preferencias y valores de cuidadores y familiares en la comunidad. De este modo, se habían liberado recursos en el hospital, lo que permitía una mayor capacidad para tratar el nuevo brote pandémico de gripe.

El programa educativo para pacientes con bajo riesgo de insuficiencia cardíaca había sido también un éxito. Estos pacientes, que generalmente no sufrían ninguna discapacidad importante, se reunían periódicamente en el centro de salud para recibir educación preventiva sobre factores de riesgo vascular y modos de vida. También se habían organizado talleres de adicción a la nicotina. De acuerdo con sus perfiles específicos, cada paciente tenía una serie de sesiones individuales, a la vez que se animaba a los pacientes con problemas comunes a agruparse. Un grupo de pacientes con insuficiencia cardíaca había conseguido, con ayuda de las autoridades locales, un espacio en el pabellón de deportes municipal para la rehabilitación cardíaca, que contaba con la supervisión de doctores a los que se les proporcionaba información acerca de cada paciente participante en el programa.

Resumen

La respuesta a las necesidades de pacientes con múltiples enfermedades crónicas representa uno de los principales desafíos para los sistemas sanitarios del siglo XXI.

El avance en este área precisa que los marcos conceptuales actuales se transformen, para que sean los individuos, su entorno y sus necesidades sanitarias el centro del sistema sanitario, en vez de la enfermedad o las necesidades de profesionales encargados de la dirección, la clínica o la política.

Este capítulo comenta los modelos existentes más destacados para mejorar la salud de pacientes que conviven con dos ó más afecciones crónicas. La adopción de tales modelos, sin embargo, requiere adaptación local, dirección y un cambio de las estrategias de gestión, para superar los múltiples obstáculos existentes en la mayoría de los sistemas sanitarios.

Los modelos de gestión de pacientes con enfermedades crónicas están relativamente en sus inicios. El Modelo de Cuidado Crónico (CCM) de Wagner, el primer sistema ampliamente divulgado y base para posteriores enfoques, lleva en uso apenas 20 años. Modelos más recientes, tales como el Modelo de Cuidado Crónico Extendido, empleado y planteado por el Gobierno de la Columbia Británica de Canadá, y el Marco de Cuidado Innovador para Enfermedades Crónicas de la OMS son, en general, variantes de ese modelo original, que enfatizan la importancia del compromiso de la comunidad, de las actividades de prevención, de promoción de salud y de la necesidad de optimizar el uso de recursos y la formulación de políticas sanitarias.

La creación de modelos válidos para pacientes con múltiples afecciones crónicas (casos complejos), que consumen un volumen desproporcionado de recursos sigue siendo un desafío sin resolver, puesto que el enfoque de todos los modelos existentes, de la mayoría de las pruebas sólidas y de las experiencias disponibles está relacionado con afecciones individuales específicas. Esto se complica con la falta de directrices clínicas prácticas y la limitada aplicabilidad de estándares para enfermedades individuales a casos con múltiples afecciones coexistentes.

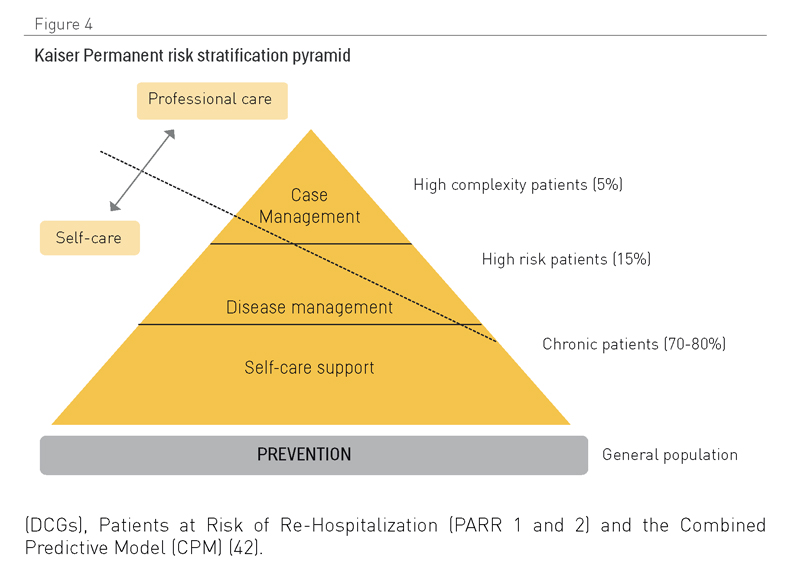

Existen otros enfoques que podrían usarse para mejorar el cuidado de pacientes con múltiples enfermedades crónicas. La estratificación basada en la pirámide de Kaiser Permanente podría facilitar la clasificación de pacientes en tres niveles de intervención, de acuerdo con su nivel de complejidad. El conjunto de pacientes que se sitúa en la parte superior de la pirámide representan sólo entre el 3% y el 5% de los casos, pero son los más complejos y consumen la porción más elevada de recursos. Por lo tanto, se les asignan a estas personas planes de cuidado integral diseñados para reducir el uso innecesario de recursos especializados, y en especial para evitar ingresos hospitalarios. Esto ha inspirado enfoques adicionales de éxito, tales como el Modelo de Cuidado Guiado, donde personal de enfermería entrenado en coordinación con un equipo médico llevan a cabo la valoración, planificación, cuidado y supervisión de casos crónicos complejos identificados por medio de modelos de predicción.

Aunque durante las dos últimas décadas se ha avanzado considerablemente en cuanto a los modelos de gestión, todavía tenemos mucho que aprender en lo referente a su aplicación a poblaciones de individuos con múltiples afecciones, particularmente en contextos socioeconómicos y étnico-culturales heterogéneos y en lo que respecta a su impacto en los recursos del sistema sanitario.

¿Por qué es este tema importante?

Un mejor conocimiento del ciclo de vida de las enfermedades crónicas y de las interacciones entre enfermedades múltiples debería conducir, por lo menos en teoría, al desarrollo de modelos de gestión eficaces. Un modelo, sin embargo, no es un libro de recetas, sino un marco multidimensional para guiar iniciativas diseñadas con el fin de abordar un problema complejo.

Se espera que los modelos específicamente diseñados para mejorar la gestión de enfermedades crónicas múltiples ayuden a frenar el crecimiento exponencial de costos asociados, y que el interés deje de centrarse en el cuidado agudo. Esto sería posible otorgando a pacientes, personas cuidadoras y a la comunidad un papel principal como agentes de cambio, con una diversificación de las funciones de profesionales de la salud, mediante la optimización de los procesos de cuidado y el uso de nuevas tecnologías, así como a través del desarrollo del ámbito de servicios más allá de los límites del sistema sanitario actual.

Tanto en países con altos como con bajos ingresos, estos modelos podrían ayudar a transformar unos sistemas sanitarios reactivos, fragmentarios y centrados en el cuidado especializado, en nuevos sistemas más dinámicos y coordinados con intervenciones con base en la comunidad.

Los modelos de cuidado también prometen ayudar a mejorar la ejecución y divulgación de intervenciones eficaces para la gestión de enfermedades crónicas (1,2), salvando multitud de barreras culturales, institucionales, profesionales y sociopolíticas (3,4,5).

Este capítulo se centra en los modelos integrales de “gestión sanitaria”, que podrían llevar a una respuesta integrada a la altura de la complejidad de los desafíos impuestos por las enfermedades crónicas múltiples (6,7).

¿Qué sabemos?

Modelos genéricos de gestión de enfermedades crónicas

El enfoque más destacado es el Modelo de Cuidado Crónico (CCM) desarrollado por Ed Wagner y asociados en el MacColl Institute for Healthcare Innovation de Seattle (EE.UU.) (8,9).

Este modelo fue resultado de un número de tentativas de mejorar la gestión de enfermedades crónicas dentro de sistemas de proveedores integrados, tales como el Group Health Cooperative and Lovelace Health System de los EE.UU. Se condujo el desarrollo de este modelo a través de revisiones sistemáticas de la bibliografía médica y de las aportaciones de un panel nacional de personas expertas, con especial atención a la importancia de replantear y rediseñar la práctica clínica a escala comunitaria.

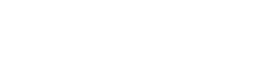

El CCM reconoce que la gestión de enfermedades crónicas es el resultado de las interacciones de tres áreas superpuestas: 1) la comunidad como grupo, con sus políticas y múltiples recursos públicos y privados; 2) el sistema sanitario, con sus organizaciones proveedoras y sistemas de seguros; 3) la práctica clínica. Dentro de este marco, el CCM identifica elementos esenciales interdependientes (Figura 1) que deben interactuar eficaz y eficientemente para alcanzar un cuidado óptimo de pacientes con enfermedades crónicas (Figura 1). El propósito último de este modelo es ubicar a pacientes activos e informados como elemento central de un sistema que cuenta con un equipo dinámico de profesionales con los conocimientos y experiencia precisos. El resultado debería ser un cuidado de gran calidad, elevados niveles de satisfacción y resultados mejorados (10,11).

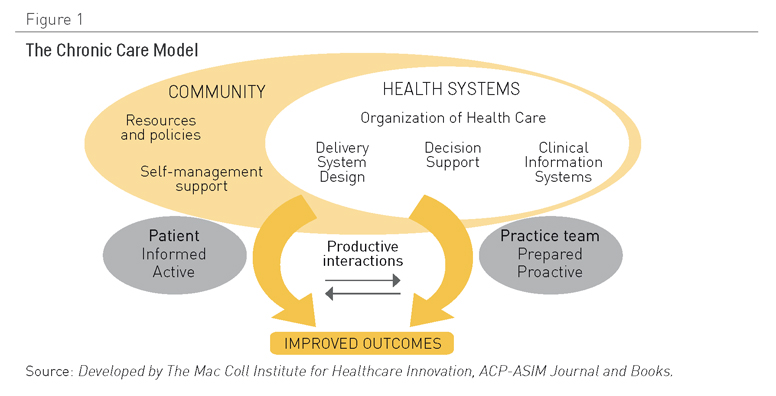

Diversos modelos han utilizado el CCM como base para posteriores desarrollos o adaptaciones. Un buen ejemplo es el Modelo de Cuidado Crónico Extendido (12) del Gobierno de la Columbia Británica de Canadá (véase Figura 2), que hace hincapié en el contexto comunitario, al igual que en la importancia de la prevención y promoción sanitaria.

Figura 1. El Modelo de Cuidado Crónico. Fuente: Desarrollado por el MacColl Institute for Healthcare Innovation, ACP-ASIM Journal and Books

|

Figura 2. El Modelo Desarrollado de Cuidado Crónico. Fuente: Ministerio de Salud, Gobierno de la Columbia Británica. Modelo Extendido de Cuidado Crónico

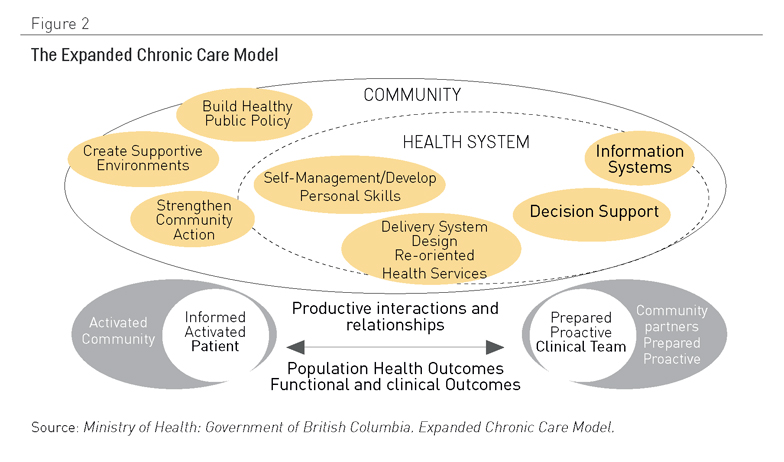

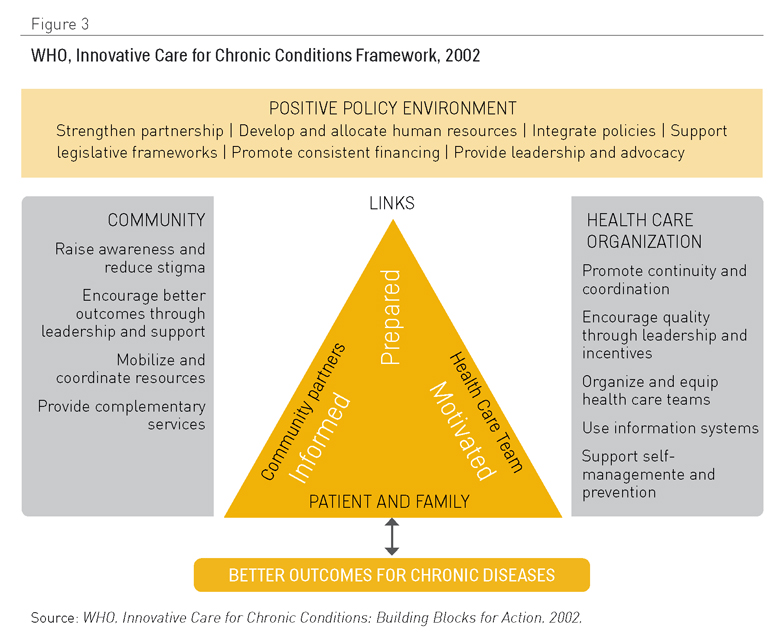

Otra adaptación popular del CCM es el modelo marco Cuidado Innovador para Enfermedades Crónicas (2,13) (Figura 3), que añade una perspectiva de política sanitaria. Uno de sus aspectos clave es el énfasis que pone en la necesidad de optimizar el uso de los recursos sanitarios disponibles dentro de un contexto geográfico y demográfico específico. Tal enfoque es crucial en muchos países de ingresos medios y bajos donde coexisten infraestructuras de múltiples proveedores, con evidentes solapamientos y un uso no óptimo de los servicios. La Tabla 1 presenta un resumen de las ideas clave que sobre las que se construye este modelo.

Tabla 1.-Elementos clave del modelo ICC

Figura 3. OMS, Marco de Cuidado Innovador para Afecciones Crónicas, 2002. Fuente: OMS, Cuidado Innovador para Afecciones Crónicas: Construcción de Bloques de Acción. 2002

El ICCC realiza contribuciones claves complementarias al CCM (14):

- A escala macro, resalta la necesidad de un ambiente político positivo para apoyar la reconducción de los servicios para orientarlos hacia las necesidades de pacientes con afecciones crónicas. Una dirección sólida, acción y colaboraciones intersectoriales, integración de políticas, sostenibilidad financiera y el suministro y desarrollo de recursos humanos cualificados representan elementos clave y constituyen una dimensión no tratada de un modo explícito en la versión original del CCM de Wagner.

- A escala media, la atención sigue estando centrada en el papel de los agentes comunitarios, así como en la importancia de la integración y en la coordinación de servicios. Mientras, cuestiones relacionadas con el apoyo de decisiones se incluyen en el suministro de recursos, para equiparar las necesidades en contextos donde existe una falta de equipamiento y medicación.

- A escala micro, la díada establecida dentro del CCM entre profesionales sanitarios y pacientes se extiende a la tríada que ahora hace partícipe a la comunidad. Se sustituye el término “activado” en referencia a pacientes por “motivado y preparado”.

- Existe un amplio consenso acerca del valor potencial del ICCC en los países con rentas bajas, a pesar del hecho de que los datos que defienden las iniciativas transformadoras impulsadas por este modelo vienen trasladados en gran medida de experiencias en países con altos ingresos y dentro del marco conceptual del CCM. A continuación, unas cuantas cuestiones destacadas de tal hecho constatado:

- Estudios apoyados a través del programa Mejorar el Cuidado de Enfermedades crónicas del Institute for Healthcare (16) ilustran que el asesoramiento externo y la participación de equipos multidisciplinares procedentes de una amplia variedad de contextos clínicos son esenciales para ejecutar el modelo con éxito. Sin embargo, factores contextuales pueden limitar el éxito y sostenibilidad de los cambios, habiéndose obtenido el mayor éxito en las experiencias de equipos grandes con buenos recursos. Se precisa mayor investigación en referencia a factores fundamentales para el éxito y en cuanto a las barreras culturales, organizativas, profesionales y derivadas de la falta de recursos, que influyen en la ejecución práctica del CCM (17,18).

- La presencia de uno o más componentes del CCM lleva a resultados clínicos mejorados y a procesos de cuidado más eficaces, habiéndose reunido la mayoría de pruebas durante la gestión de la diabetes, insuficiencia cardíaca, asma y depresión (11). Extrapolando resultados de la aplicación del modelo de gestión de la diabetes a nivel demográfico, se podría esperar una reducción de la mortalidad de más de 10% (19). Se han asociado todos los componentes del modelo a mejoras clínicas y de procedimiento, con la excepción del componente referente al apoyo de la comunidad, para el cual no hay información suficiente. Los dos componentes individuales con mayor eficacia parecen ser el rediseño de la práctica clínica y el apoyo al autocuidado (20,21). Aunque sería un reto evaluar el CCM en su totalidad como una intervención integrada de componentes múltiples, se ha demostrado que una mayor estandarización del cuidado primario con CCM conlleva una relación positiva con procesos e indicadores clínicos mejorados (22,23).

- Aunque la filosofía de un enfoque integrado, de facetas múltiples, es integral al CCM, esto no implica necesariamente que cada tipo posible de intervención tenga el mismo grado de eficacia. Es útil cuestionarse qué componentes son necesarios, suficientes o más importantes para una estrategia de facetas múltiples. Es particularmente importante preguntarse por organizaciones que puedan ser incapaces de ejecutar todos los componentes del modelo de un modo simultáneo, y que necesitan una orientación sobre qué intervenciones introducir primero, después o (quizás) no incluir. Algunas intervenciones, por ejemplo el rediseño de los sistemas de entrega, pueden tener efectos positivos por ellas mismos, mientras que otras, por ejemplo los sistemas de información clínica, pueden ser beneficiosas sólo cuando se utilizan como apoyo y ayuda de otras intervenciones.

- Los estudios iniciales de Parchman et al. evitaron diferenciar los efectos de los distintos componentes del CCM, pero dos estudios más recientes de Parchman y Kaissi sí que realizaron esta diferenciación. Estos estudios descubrieron que los diferentes componentes CCM presentaban una relación directa con diferentes resultados (control de HbA1C y comportamiento de autocuidado), mientras que los sistemas de información clínica estaban inversamente24,25).

Aunque los estudios del impacto económico del CCM son limitados, se han obtenido datos de ahorro y eficacia de costos para pacientes diabéticos (26-28).

CCM y enfermedades crónicas múltiples

Aunque el enfoque integrado y holístico del CCM es parejo a la realidad de las enfermedades crónicas complejas, hay muy pocas pruebas de su aplicabilidad y eficacia en esta área (6,29).

Esto se acentúa con la ausencia de pautas clínicas prácticas que aborden las afecciones múltiples, o que estén diseñadas para permitir a los profesionales de cuidado primario considerar las circunstancias individuales y preferencias de los pacientes con enfermedades crónicas múltiples (30).

Además, existe la necesidad de estándares de calidad para servicios destinados a pacientes con afecciones crónicas múltiples, particularmente en relación con la coordinación del cuidado, a la educación de pacientes y cuidadores, a la capacitación en el apoyo al autocuidado y a decisiones compartidas, al tiempo que se toma en consideración las preferencias y circunstancias individuales.

En la raíz del las lagunas de conocimiento existentes está el hecho de que los pacientes con polipatologías a menudo son excluidos de los ensayos clínicos (31). En palabras de Upshur, « lo que es bueno para la enfermedad puede no ser bueno para el paciente» (32).

Con este escenario, no es sorprendente que la realidad de los pacientes crónicos complejos haya desempeñado un papel decisivo en el desarrollo de otra muy significativa adaptación del CCM: El Modelo de Cuidado Guiado. En este modelo, el personal de enfermería de cuidado primario, en coordinación con un equipo médico, se ocupa de la evaluación, planificación, cuidado y seguimiento de los pacientes crónicos complejos identificados por medio de un modelo de predicción. Los datos preliminares obtenidos a partir de un ensayo controlado aleatorio de grupo sugiere que este enfoque lleva a una mejora en los resultados sanitarios, a la reducción de costos, a una menor carga sobre cuidadores y familia, así como a mayores niveles de satisfacción entre los profesionales sanitarios (33-36).

Estratificación de riesgos y gestión de casos

La estratificación de riesgos significa la clasificación de los individuos en categorías, de acuerdo con la probabilidad de que sufran un deterioro de su salud.

El sistema más ampliamente utilizado para la estratificación se conoce como la Pirámide de Kaiser (Figura 4), desarrollada por Kaiser Permanente en los Estados Unidos, para clasificar a pacientes en tres categorías de niveles de intervención, dependiendo de su nivel de complejidad. En la base de la pirámide, Kaiser ubica a los miembros sanos de la población para los que la prevención y el diagnóstico temprano de la enfermedad son las prioridades. En el segundo nivel, donde las personas tienen algún tipo de enfermedad crónica, el interés se orienta al autocuidado, la administración apropiada de medicamentos y la educación en aspectos sanitarios. En el tercer nivel, a pacientes identificados como complejos (del 3% al 5% del total) se les asignan planes de cuidado guiados por proyectos de gestión de caso diseñados para reducir el uso inadecuado de servicios especialistas y evitar ingresos hospitalarios.

Algunos sistemas sanitarios públicos europeos, entre los que destaca el Servicio Sanitario Nacional (NHS) de Reino Unido, han tratado de aplicar el modelo Kaiser en sus contextos (37-39).

El método utilizado para identificar a personas con enfermedades complejas varía de un modelo a otro. El NHS trató de adaptar el modelo estadounidense Evercare (véanse los detalles abajo) pero debido a la falta de datos disponibles, se tenía que identificar a pacientes usando criterios de selección (40). Otros, más tarde, siguieron el modelo de predicción (41), mediante el uso de un amplio número de métodos tales como el Modelo Ajustado Clínico de Predicción de Gruposel Grupos de Costo Diagnóstico (DCGs), Pacientes con Riesgo de Reingreso Hospitalario (PARR 1 y 2) y el Modelo de Predicción Combinado (CPM) (42). (ACGs-PM),

Figura 4.- Pirámide de estratificación de riesgos de Kaiser Permanente.

Con independencia del enfoque, el paso inicial es la recopilación y análisis de bases de datos de costos, datos clínicos y demográficos para establecer, para una persona concreta o grupo de personas, el riesgo de sufrir una enfermedad específica o un incidente asociado con el deterioro de su salud (43).

El caso más frecuentemente calculado es el ingreso hospitalario no programado, aunque se pueden utilizar muchos otros, tales como las visitas a servicios de urgencias, costos de medicinas y pérdida de independencia. La estratificación puede también realizarse con base al grado de presencia entre las diferentes poblaciones de factores de riesgo, debido a estilos de vida poco saludables (44).

La técnica de estratificación de riesgos nació debido a razones económicas, a medida que las empresas aseguradoras comenzaron a utilizarla para crear diferentes productos o primas, de acuerdo con el perfil de riesgo de sus clientes, a la vez que evitaban la introducción de modelos que rechazaban individuos a causa de afecciones previas. En los sistemas sanitarios nacionales, el ajuste y estratificación de riesgos permite la asignación diferencial de servicios y actividades sanitarias (preventiva, correctora o compensatoria) y recursos, con el fin de evitar una sobrecarga grave del sistema. En pocas palabras, los modelos de estratificación de riesgos permiten la identificación y gestión de individuos que precisan las actuaciones más intensivas, tales como personas ancianas con múltiples afecciones complejas. En estos casos en particular, la estratificación busca evitar ingresos hospitalarios no programados (45), optimizar la asignación de recursos (46), promover el autocuidado del paciente (47), priorizar la intensidad de intervenciones en todos los entornos (48) e incluso puede usarse para seleccionar participantes en ensayos clínicos (49).

Aunque la crecientemente extendida aplicación de archivos sanitarios electrónicos está facilitando la estratificación de riesgos, todavía es difícil alcanzar en todos los entornos la disponibilidad de información precisa con bajas tasas de pérdida de datos. En muchos casos, los recursos deben invertirse en la transformación de datos para usos analíticos. En otros, la clasificación de enfermedades es una importante fuente común de distorsión. La mala clasificación, por ejemplo, con el uso de códigos de Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades (CIE, International Classification of Diseases (ICD) ha sido descrita en hasta el 30% depacientes (50).

Existen problemas que surgen de la compleja afección en sí misma. Generalmente se evalúa la comorbilidad con el uso de escalas que de algún modo suman el número de enfermedades padecidas por una persona, cuya contribución al total varía dependiendo de su gravedad, tales como en Índice Charlson (51) (Capítulo 3). Algunos grupos han propuesto la selección de grupos de pacientes complejos por medio de asociaciones de enfermedades específicas (52), aunque otros alegan que las combinaciones de enfermedades específicas son de menor relevancia que la carga de la comorbilidad (53).

La estratificación por fragilidad o enfermedad también ha resultado útil durante los desastres naturales, tales como el Huracán Katrina en Nueva Orleáns. Aunque se emplearon estrategias de evacuación estratificadas según el nivel de ingresos económicos, personas ancianas y con enfermedades crónicas dentro de cada uno de los estratos sociales tenían menos opciones de evacuación que las personas sanas (54).

La estratificación también está promoviendo el creciente interés en la gestión de casos, un concepto con origen en el cuidado de casos psiquiátricos no ingresados en los Estados Unidos en la década de los 50. La gestión de casos es una intervención compleja, que generalmente lleva a cabo personal de enfermería y que abarca un amplio espectro de intervenciones que incluyen la identificación del paciente, la evaluación de sus problemas y necesidades, la planificación del cuidado de acuerdo con tales necesidades, la coordinación de servicios, la revisión, supervisión y adaptación del plan de cuidado. Normalmente, se promueve la gestión de casos, bien como un elemento clave, bien como un complemento a otros elementos dentro de enfoques de componentes múltiples (55-57).

Evercare es la piedra angular de uno de los más extendidos programas de coordinación de atención sanitaria de los Estados Unidos, con más de 100.000 individuos actualmente de alta a lo largo de 35 estados (58). Sus principios básicos son:

- El enfoque integral individual al cuidado geriátrico es esencial para promover el mayor nivel de independencia, bienestar y calidad de vida, así como para evitar efectos secundarios de la medicación (con atención a la medicación múltiple).

- El principal proveedor es el sistema de atención primaria. Profesionales mejor ubicados para poner en práctica el plan es el colectivo de enfermería con base en la comunidad que actúan como agentes clínicos, colaboradores, educadores de pacientes, coordinadores y consejeros. Sólo un tercio del tiempo de trabajo es dedicado al cuidado directo de pacientes (59).

- Se facilita el cuidado sanitario del modo y en el contexto menos invasivos.

- Las decisiones se apoyan en datos registrados mediante el uso de plataformas.

El primer paso del modelo es la identificación de pacientes geriátricos con alto riesgo, para los que se elabora un plan de cuidado individual. Se asigna al personal de enfermería de cuidado primario avanzado una lista de pacientes a los que supervisan de un modo regular. Son responsables de proporcionar cuidado adicional, incluidos los ingresos en residencias u hospitales.

En el modelo Evercare, profesionales de enfermería dirigen y proporcionan cuidado con especial atención al bienestar psicosocial. Profesionales de medicina participantes, deben tener experiencia y conocimientos de geriatría, particularmente en el cuidado de pacientes frágiles. Se minimiza la transferencia de cuidado sanitario y aumenta la proporción de dicho cuidado recibido en residencias de mayores. Se ponen en marcha la detección temprana y programas de seguimiento con equipos que actúan como representantes del paciente, en un intento de obtener el máximo beneficio en el cuidado por parte de su seguro médico. La familia participa en el cuidado del paciente, existiendo una comunicación intensa y continua entre la familia y el equipo profesional implicado.

Una evaluación del sistema ha mostrado reducciones del 50% en las tasas de ingresos hospitalarios, sin haber aumentado la mortalidad y con ahorros de costos, así como grandes niveles de satisfacción (60).

A la vista de este éxito en los EE.UU, en 2003 el Servicio Nacional de Salud Británico (NHS) decidió probar el modelo Evercare en 9 Fundaciones de Atención Primaria (61). Un análisis preliminar identificó una población de gran riesgo que incluía a pacientes con dos o más ingresos hospitalarios durante el año anterior. Este grupo representaba el 3% de la población de más de 65 años, pero significaba el 35% de los ingresos hospitalarios no programados para esa banda de edad. Sorprendentemente, muchos de estas personas no estaban siendo tratados de un modo activo por el sistema: sólo el 24% de ellos estaban registrados como casos por el personal de enfermería del distrito y sólo un tercio de ellos eran conocidos por los servicios sociales. Curiosamente, el 75% de la población de alto riesgo vivía en la comunidad y sólo el 6% y 10% en residencias de mayores y centros de cuidado geriátrico, respectivamente. El uso de una versión adaptada del Evercare con atención a la comunidad en el NHS, y las diferencias entre los contextos de cuidado sanitario en los Estados Unidos y Reino Unido, puede haber conducido a lo que parecían resultados muy diferentes. Una evaluación formal a través de experimentos pilotos no mostró una reducción de los ingresos hospitalarios urgentes, de las estancias hospitalarias medias, ni de la mortalidad (62). Sin embargo, la evaluación sí presenta muchos problemas (63), y el aparente fracaso del programa Evercare en Inglaterra puede deberse simplemente a que no ha habido tiempo suficiente para llevar a cabo el programa por completo (transcurrieron varios años en los Estados Unidos hasta que se consiguieron reducir los ingresos hospitalarios) o porque no se seleccionaron al conjunto de pacientes del modo adecuado. A pesar de los fracasos, el NHS ha mantenido la gestión de casos de personas ancianas frágiles con enfermedades crónicas complejas. Esto puede ser, en parte, porque la evaluación cualitativa elaborada por el mismo grupo independiente que preparó el estudio cuantitativo mostró que el programa gozaba de gran aceptación tanto entre pacientes, personas cuidadoras, como entre profesionales de enfermería y de medicina implicados (64).

¿Qué hay que saber?

Aunque hay pruebas crecientes de la eficiencia y eficacia de las intervenciones relacionadas con la gestión de casos crónicos (7, 11, 14, 65-72) (Tabla 2), existe poca información específicamente relacionada con el impacto de los modelos de cuidado para la gestión de diferentes combinaciones de enfermedades complejas.

Algunos resultados decepcionantes de la aplicación del modelo Evercare en la NHS británica, junto con los de algún modo prometedores nuevos datos que defienden la gestión de casos para personas de la tercera edad vulnerables (70,74-76), subrayan la necesidad de realizar más esfuerzos para entender el papel de los modelos de cuidado en la gestión de enfermedades crónicas múltiples (77). Tales esfuerzos deberían centrarse en:

· La aplicabilidad e impacto de diferentes modelos en diversos contextos.

· El desarrollo de un lenguaje sistemático para los diferentes elementos de los modelos.

· La estandarización de intervenciones.

· La evaluación comparativa de los beneficios de intervenciones múltiples frente a intervenciones aisladas.

· La puesta en marcha de estrategias para facilitar una ejecución rápida con éxito y divulgación.

· Su impacto económico y eficacia.

Tabla 2. Intervenciones eficaces en la gestión de pacientes crónicos (realizado por los autores)(7, 11, 14, 65-72).

- Modelos y programas integrados de gestión de enfermedades (del tipo del CCM)

- Programas de gestión de enfermedades para afecciones específicas: diabetes, insuficiencia cardíaca, etc.

- Iniciativas de integración y coordinación de servicios.

- Refuerzo de la atención primaria.

- Apoyo y promoción del autocuidado.

- Evaluación geriátrica.

- Identificación de grupos con mayor riesgo de hospitalización.

- Programas de alta hospitalaria temprana para enfermedades específicas.

- Desarrollo del papel del personal de enfermería.

- Supervisión a distancia.

- Intervenciones multidisciplinares.

¿Qué estrategias innovadoras podrían acortar las distancias?

Las opiniones sobre la innovación en los modelos de gestión de enfermedades crónicas oscilan entre dos extremos, desde las predicciones más optimistas en cuanto a su impacto (78) (reducción en la mortalidad y uso de recursos, con ahorros netos al sistema), a las más escépticas, que cuestionan si merecen la pena (79).

Tal como se apunta anteriormente, hay pruebas que defienden en general la eficiencia y eficacia de las intervenciones individuales (80-87), pero todavía hay una falta de estandarización en casi todos los aspectos de estas intervenciones. Algunas prestigiosas organizaciones han propuesto el uso de una taxonomía estándar (88), y existen proyectos con el propósito de enriquecer esto centrando la atención en las enfermedades múltiples (89).

La cooperación, especialmente entre las instituciones, más allá de fronteras nacionales y culturales, resulta esencial para evitar el solapamiento de esfuerzos, para fomentar el debate público y para promover un cambio eficaz de políticas. Las nuevas tecnologías deberían desempeñar un papel importante, no sólo a la hora de facilitar encuentros y comunicaciones de larga distancia, sino también para promover el diseño y ejecución de estudios multicéntricos que usen medidas estandarizadas.

Aunque el contexto para los esfuerzos transformadores es muy favorable, introducir cambios a gran escala en los sistemas de salud para alcanzar los desafíos impuestos por las enfermedades crónicas complejas precisará planificación, cambios de gestión y esfuerzos coordinados a todos los niveles dentro del sistema sanitario.

Para conseguir cualquier cambio significativo, la política, los agentes de financiación y las direcciones de cuidado sanitario deberían tener una visión renovada del sector y entender que el campo de juego ahora implica sistemas complejos de adaptación, que han hecho que las soluciones tradicionales resulten irrelevantes. Profesionales de la salud y pacientes ya no pueden ser considerados componentes predecibles y que se pueden estandarizar dentro de un sistema impersonal.

La complejidad de este cambio deseado del sistema puede ilustrarse de un mejor modo con un ejemplo. Los estudios indican que el 76% de los reingresos hospitalarios son evitables (90) en los 30 días posteriores alta. Esto representa el 13% de los ingresos en un hospital de día moderno, una alta proporción de los cuales son pacientes crónicos complejos frecuentes (Capítulo 3).

Las pruebas indican que se podría rectificar esta situación mediante factores como: una reducción en el índice de complicaciones durante las estancias hospitalarias, la mejora de la comunicación en el proceso del alta hospitalaria, una supervisión cercana y una participación activa de pacientes en casa, así como una mejor comunicación y cooperación entre el hospital y la atención primaria después del alta. Una atención continua óptima podría hacer alcanzar estos resultados, como consecuencia de procesos de cuidado integrado que garantizan que las personas permanecen en comunicación y siguen supervisados después del alta, y que las personas encargadas de la gestión junto con profesionales sanitarrios trabajan sin fisuras a lo largo de la comunidad hospitalaria (Capítulo 6). Desgraciadamente, la mayor parte de los sistemas en todo el mundo continúan funcionando con políticas muy centralizadas y procedimientos que nutren un modelo tradicional de cuidado agudo, en el que los hospitales controlan un ecosistema fragmentado de servicios.

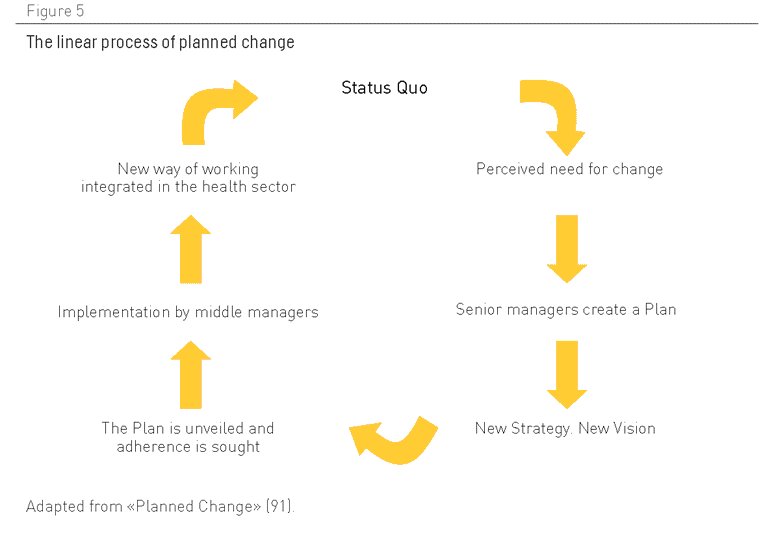

Con la inminente pandemia de enfermedades crónicas, y con los nuevos desafíos creados por los casos complejos, es imperativo aunar los niveles de dirección y compromiso para cambiar y abandonar el usual proceso lineal de cambio programado que domina la mayoría de sistemas (Figura 5).

Figura 5. El proceso lineal de cambio programado. Adaptado de “Cambio Programado”(91)

Los tiempos han cambiado. Este enfoque de planificación, que cuenta con una gran presencia, refleja una visión excesivamente simplista del modo en el que las organizaciones trabajan hoy en día. Aunque se aplica con la mejor de las intenciones, con el propósito de reorganizar el sector basándose en la jerarquía y la planificación lineal descendente, este enfoque está desfasado y refleja las condiciones de una era de gestión derivada de la época industrial, con directivas centrales en una organización que define la estrategia, que crea estructuras y sistemas para influir en lo que se ha llamado “hombres de organización” (92).

Ésta es una filosofía que espera un alto grado de conformismo de sus recursos humanos, pero desde hace tiempo esto ya no se corresponde con la situación en el sector de la salud, donde el conjunto de profesionales sanitarios y de administraciones locales están crecientemente distanciados y desconectados de los aparatos de gestión y elaboración de políticas centrales del sistema.

Hoy en día, el cambio sólo será posible a través de la dirección local y la participación entusiasta de profesionales, de la administración de la salud y del público dentro del sistema de cuidado sanitario. Esto demanda también una mayor complejidad en la gestión/planificación del sistema, para permitir a profesionales y personas usuarias desempeñar un papel mucho más estratégico en el desarrollo y mejora de los modelos que se ajusten a las necesidades de pacientes con múltiples enfermedades crónicas. Esto es claramente un cambio cultural complejo para el que no existe una fórmula mágica.

Como ocurre con cualquier otro sistema complejo, se necesitarán pasos progresivos para reconstruir el sistema desde los cimientos, mientras se recurre al capital intelectual de profesionales de primera línea, administradores, pacientes y sus seres queridos. De hecho, se ha demostrado que los cambios más substanciales y sostenidos han tenido lugar en aquellas organizaciones que permiten el cambio desde abajo instigado por personas usuarias de primera línea, profesionales y la dirección (93).

Tal como se sugiere anteriormente, aquellas personas responsables de la elaboración de políticas deben dedicar mayores esfuerzos a permitir que el conjunto de trabajadores de las diversas partes de la organización (atención primaria y hospitalaria en particular) creen nuevos modos de trabajar conjuntamente y generen comunidades de práctica que estimulen el cambio organizativo. La idea es promover la iniciativa entre profesionales y la administración local, en vez de esperar que se pongan en marcha los guiones diseñados por estamentos superiores.

Esta forma más descentralizada de dirección no implica sacrificar los beneficios conseguidos en los años recientes, a través de una gestión directa y centralizada. Tampoco significa una vuelta al pasado, a un sistema en el que sus profesionales no tienen responsabilidades y no necesitan dar cuentas. En un sistema descentralizado, los que elaboran las políticas centrales y la dirección deben actuar y ser percibidos como agentes motivadores, promotores de interrelaciones a todos los niveles, que facilitan los contactos. Uno de sus papeles principales en un sistema moderno debería ser el refuerzo de incentivos para alentar a los equipos de profesionales sanitarios, administradores y miembros del público locales a experimentar con mejoras propias, facilitando la disponibilidad de recursos, analizando y comparando resultados y difundiendo las lecciones aprendidas por ellos a otros equipos dentro del sistema.

Otro papel fundamental para las personas responsables de elaborar políticas y para las direcciones centrales sería la creación de mecanismos para apoyar la formación de gestión y la promoción de dirección local. Las personas encargadas de la dirección local necesitan conocer, entre otros aspectos: cómo motivar a sus equipos, construir sistemas, involucrar a la comunidad en una gestión de cambio y armonizar las iniciativas locales con estrategias generales perseguidas por la organización global. En el País Vasco (España), por ejemplo, se ha creado una organización para cumplir este papel. Esta organización, conocida como O+Berri, tiene como una de sus funciones principales la promoción de las comunidades con las mejores prácticas dentro de la organización. A este respecto, la agencia también promueve la conectividad entre las diferentes comunidades con las mejores prácticas, a la vez que ayuda a la dirección del sector a analizar tendencias para optimizar sus estrategias, con el fin de divulgar las innovaciones y políticas a lo largo de todo el sistema.

El punto fuerte de esta forma más descentralizada de dirección y administración reside en aprovechar la capacidad intelectual del sistema y abandonar la falsa ilusión de que es posible idear un único modelo operativo para toda una región o país. Dentro de tal sistema, deberían considerarse las diferencias que existen entre las organizaciones como algo positivo, no como un inconveniente, con líderes de todos los niveles persiguiendo sin descanso nuevos modos de facilitar y permitir mejoras en los contextos que sean más receptivos a tales cambios, gracias a su esfuerzo y compromiso colectivo.

Además, necesitamos más inversiones y una búsqueda activa de nuevas ideas que se incorporen a los modelos, con formas más audaces de evaluación, que permitan una curva de aprendizaje más pronunciada (el modelo de ensayo clínico es perfecto para aislar efectos simples, pero resulta menos útil para el aprendizaje de experiencias complejas). Las nuevas formas deberían incluir la evaluación participativa que tome en consideración las perspectivas y expectativas de profesionales y personas usuarias. En contextos complejos, las técnicas de investigación cualitativas pueden abrir el camino de un modo más eficaz que las técnicas cuantitativas, que siempre estarán sujetas a subjetividades, al omitir aspectos significativos para los que no hay datos disponibles.

Lo que se necesita es un espíritu pionero para ir más allá de los modelos existentes. Quizás el cambio más radical se necesita (en el sentido de tratar con la raíz) en formas culturales de tratar con la responsabilidad de las personas en lo referente a su salud y enfermedad. Lo que falta es un compromiso claro con la capacidad de las personas de adquirir conocimiento, cambiar su conducta y permitirles escoger con libertad.

Contribuyentes

Rafael Bengoa, Francisco Martos y Roberto Nuño escribieron el primer borrador de este capítulo en español y aprobaron su traducción al inglés. Alejandro Jadad revisó con detalle la traducción al inglés y la aprobó antes de publicarla para colaboraciones externas a través de la plataforma OPIMEC en ambos idiomas. Sara Kreindler, Tracy Novak y Rafael Pinilla aportaron importantes contribuciones, que Richard Smith incorporó a una versión revisada del capítulo, la cual fue aprobada por los otros colaboradores. Alejandro Jadad realizó las revisiones finales y aprobó la versión que fue incluida en el libro en soporte papel.

Los contribuyentes son los responsables del contenido, que no representa necesariamente el punto de vista de la Junta de Andalucía o de cualquier otra institución que haya participado en este esfuerzo conjunto.

Agradecimientos

Francisca Domínguez Guerrero y Rodrigo Gutiérrez realizaron intuitivos comentarios a este capítulo que no se tradujeron en cambios de su contenido

Cómo citar este capítulo

Bengoa R*, Martos F*, Nuño R*, Kreindler S, Novak T, Pinilla R. [*Contribuyentes principales] Management models. En: Jadad AR, Cabrera A, Martos F, Smith R, Lyons RF. When people live with multiple chronic diseases: a collaborative approach to an emerging global challenge. Granada: Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública; 2010. Disponible en: http://www.opimec.org/equipos/when-people-live-with-multiple-chronic-diseases

Licencia Creative Commons

Modelos de gestión por Bengoa R, Martos F, Nuño R está bajo licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 3.0 España License.

- Formación en "Mejora en la atención a personas con enfermedades crónicas"

- Mejora en la atención a personas con enfermedades crónicas (2ª edición)

- Mejora en la atención a personas con enfermedades crónicas (1ª edición)

- Cuando las personas viven con múltiples enfermedades crónicas: aproximación colaborativa hacia un reto global emergente