Comentarios de Prevención y promoción de la salud

Prevención primaria: ¿Tratar a grupos de población o a pacientes individuales?

La prevención primordial se centra en la salud de la población; sin embargo, si pasamos a la prevención primaria, entonces se puede poner el interés en las personas y en sus familias. A la mayoría de trabajadores sanitarios de nuestra sociedad contemporánea lo que les interesa es tratar a pacientes individuales y a sus familias.

Las personas con una enfermedad establecida tienen un alto riesgo por definición, pero también se puede calcular el riesgo para las personas que no tienen una enfermedad establecida. Hay polémica en torno a cuál es la mejor manera de calcular el riesgo y a qué nivel se debe tratar a las personas. La OMS recomienda calcular el riesgo cardiovascular utilizando gráficas que combinen factores de riesgo, como la edad, ser fumador o no, o si la persona tiene o no diabetes y presión sanguínea sistólica (17). Las gráficas para países que cuentan con muchos recursos también incluyen niveles de colesterol en la sangre, pero hay gráficas que excluyen el colesterol para los lugares en los que es imposible o resulta prohibitivo acceder a los laboratorios para que midan los niveles de colesterol. Utilizar este tipo de gráficas tiene sentido porque ofrecen un cálculo del riesgo mucho más preciso que utilizando cualquier otro factor individualmente, aunque algunos expertos argumentan que la edad es un factor determinante del riesgo tan decisivo que se puede utilizar por si solo (Nick Wald, comunicación personal, pendiente de publicación).

Estas gráficas se desarrollan utilizando datos extraídos de los famosos estudios de Framingham, en Estados Unidos, donde se ha realizado el seguimiento de un importante grupo de población durante años. Algunos expertos argumentan que no es adecuado utilizar los datos de Framingham para otros países, donde la composición de la población puede ser muy diferente. El Reino Unido, por ejemplo, que probablemente tenga una población que es menos diferente de la de Framingham que muchos otros países, ha utilizado informes electrónicos para generar una nueva herramienta de valoración de riesgo llamada QRISK, que ha demostrado hacer mejores predicciones para el Reino Unido que la herramienta de Framingham (18, 19).

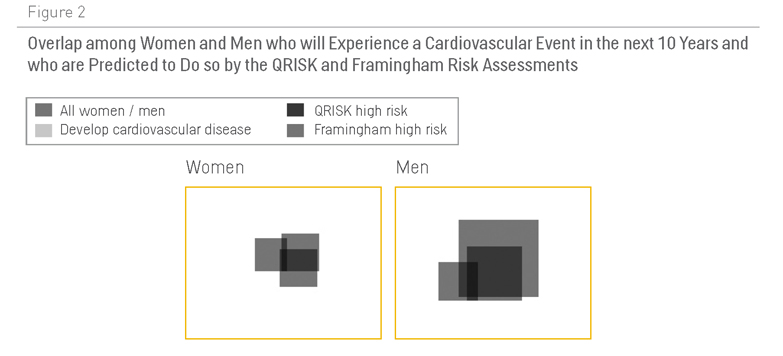

Figura 2. Superposición entre mujeres y hombres que sufrirán un acontecimiento cardiovascular en los próximos diez años a partir de las predicciones de QRISK y de las valoraciones de los riesgos de Framingham

Sin embargo, la figura 2 muestra que ninguna de las dos herramientas es demasiado buena para calcular el riesgo a nivel de la población. QRISK identifica un 10% de hombres con un “riesgo alto” (con un 20% de probabilidad de sufrir un acontecimiento cardiovascular en los próximos diez años), pero solo el 30% de los acontecimientos cardiovasculares los sufrirán esos hombres (18). En otras palabras, el 70% de los acontecimientos cardiovasculares los sufrirán hombres definidos como de bajo riesgo porque constituyen el 90% de la población. En el caso de las mujeres, es peor: QRISK identifica un 4% de mujeres de alto riesgo, pero solo el 18% de los acontecimientos cardiovasculares se dan en este grupo (19).

La OMS recomienda mejorar el estilo de vida de las personas en todos los niveles de riesgo, así como controlar regularmente a las que tienen entre un 10% y un 20% de riesgo, y someter a tratamiento farmacológico a los pacientes con un riesgo superior al 20%. El Instituto Nacional de Salud y Excelencia Clínica de Inglaterra y Gales recomienda las mismas medidas (20). La Asociación Americana del Corazón recomienda una dosis baja de aspirina para pacientes que tengan más del 10% de probabilidad de sufrir un acontecimiento cardiovascular en los próximos diez años (21). Un estudio sistemático reciente indica que puede que estos consejos sean erróneos (22).

Pero existe el argumento de que un 20% de probabilidad de sufrir un acontecimiento cardiovascular en los próximos diez años es un riesgo alto inaceptable para algo que fácilmente puede tener como consecuencia la muerte o una discapacidad grave. La gente gasta grandes cantidades de dinero cada año para asegurar sus casas, que no tienen ni de lejos una probabilidad del 20% de incendiarse o de sufrir daños graves en los próximos diez años. Por supuesto, el riesgo de un daño potencial se debe calcular contra el riesgo que conlleva el tratamiento, y por este motivo los autores del estudio sistemático reciente se muestran en contra de utilizar aspirina en personas con un riesgo bajo (22): sin duda, la aspirina reducirá las posibilidades de sufrir una trombosis que provocaría un ataque al corazón o un infarto, pero también aumenta el riesgo de una hemorragia gastrointestinal o cerebral, con lo que el riesgo del tratamiento anula cualquier posible beneficio.

Comentarios existentes

Siempre será mas rentable la intervención grupal.

El seguimiento ha de ser individual, pero considero fundamentales las actividades grupales, tanto por su rentabilidad como por el hecho de la motivación sobre los pacientes o sus cuidadores.

Es importante realizar un abordaje individual de cada paciente además de realizar Decisiones compartidas con el paciente con el fin de que nuestras medidas sean mucho mas efectivas y eficientes aunque debemos tener cuidado con no realizar una medicalizacion de nuestras consultas de atención primaria.

Seria de interés realizar un apartado en este capítulo sobre la prevencion cuaternaria

La prevención primaria para quienes no tienen enfermedad, es la piedra angular. Las intervenciones en este campo deben dirigirse a la comunidad, al grupo.

No es entendible que la prevención primaria no se esté ya realizando en los niños, una asignatura seria de cocina , de ejercicio como parte de las actividades normales de la vida diaria, de autocuidado, podrían ayudarnos mucho más que el control de los niveles de colesterol y serían bastante baratas. ¿Por qué no lo estamos haciendo?

Estoy de acuerdo con que la prevención primaria ha de empezar lo antes posible. Yo me atrevería a decir que tan pronto como la mujer esté embarazada, hay que concienciarla y educarla en el tema de enfermedades crónicas. Está demostrado que hay condiciones (malnutrición, estres, hypertensión, diabetes…) que ocurren durante el embarazo que predisponen a que el niño desarrolle enfermedades crónicas en la vida adulta (hipótesis de Barker). Pero tambien la nutrición durante los primeros años de vida es muy importante y los hábitos que desarrolle el individuo, desde muy temprana edad, son determinantes del desarrollo de estas enfermedades más adelante.

No debemos olvidar que estamos hablando de PREVENCIÓN PRIMARIA.

Desde el punto de vista de la Salud Pública, el procedimiento de tratar con fármacos a personas "aparentemente sanas", creo que es cuanto menos descabellado.

Respecto a las enfermedades crónicas, como con cualquier otro problema de salud, la prevención primaria se debe hacer a dos niveles:

1. Poblacional; instando a gobiernos y a todo el tejido socioeconómico de los paises a promulgar políticas y actuaciones saludables. Sin olvidarnos de la educación en las primeras edades de la vida. Puede que los resultados a corto plazo sean pobres, pero debe ser mirada como una inversión de futuro.

2. Individual; en este caso, las intervenciones se deben realizar en las persona que más se van a beneficiar de ellas. Para ello, existen herramientas (que pueden ser mejorables, pero son las que hay) que definen ese grupo de población.

Salu2

“La alfabetización sanitaria es el grado de capacidad que tienen los individuos tienen la capacidad de obtener, procesar y comprender la información y los servicios de salud básicos necesarios para tomar decisiones apropiadas en materia de salud.”

Healthy People, 2010

ALFABETIZACIÓN SANITARIA y EMPODERAMIENTO

“La alfabetización en salud significa algo más que ser capaz de leer los folletos y concertar visitas médicas con éxito. Mejorando el acceso a la información de salud y su capacidad de utilizar esta misma información de manera eficaz por parte de la población, la alfabetización de la salud es fundamental para el empoderamiento de las personas.”

Jacobs et al., 2005

Prioritaria en salud pública, en grupos de población sí e individual también, ambas pueden ser autónomas por parte de las personas o "tuteladas" por profesionales de la salud